My Torrid Summer of Pasta and Wine

"A way to rebel at the table against a lifestyle that oppresses humanity at every turn."

Life is a combination of magic and pasta. In food circles, this oft-quoted line by Federico Fellini has achieved nearly “Live Laugh Love” status. Perhaps it is hanging in your kitchen? Well, just because the sentiment is framed and sold on Etsy doesn’t make it any less true.

As you may be aware, my obsession with pasta nearly matches my obsession for obscure grapes or niche spirits. Earlier this summer, for instance, I wrote a very long memoir about my three-decade relationship with marubini.

Still, my love affair with pasta is rather polyamorous, and I regularly have infatuations with other dishes. The other day I wrote about my love of pasta al limone, the traditional lemon pasta of Sicily. The past few summers, as eggplant season arrives, I’ve been chasing another sultry, sensual Sicilian dish, pasta alla norma (recipe below).

Yet my eye still wanders. Every year, when I see broccoli rabe in the farm market, I have a fling with orecchiette con cime di rapa. I’ve talked at length about my turbulent relationship with pesto in my essay “God and Pesto are Dead.” For a while, I was also obsessed with perfecting another traditional Ligurian dish, salsa di noci , a walnut sauce that should honestly be just as famous as pesto (that recipe is also below).

Then there are kinkier dalliances. A few years ago, when I was working as a clickbait chronicler of food trends, I became briefly infatuated with a dish called called Dirty Martini Pasta, which had gone somewhat viral on TikTok at the time. As I explained in my article:

Just like everything bagel seasoning or bourbon-flavored stuff, “dirty martini” has become a super popular flavor descriptor for food beyond cocktails. We’ve seen the rise of dirty martini salads and dirty martini deviled eggs, for instance. So dirty martini pasta just makes sense.

Despite a catchy name, Dirty Martini Pasta (recipe below) at least has its basis in classic pasta flavors—olive, lemon, garlic, parsley, oil, butter. The only element that might make an Italian mad is the optional crumbling of blue cheese—or perhaps the de-glazing of the saucepan with gin.

During that period of my life, I was writing about all sorts of mashups or hacks that had several millions views on TikTok: crispy sushi rice waffles, vodka butter, cowboy butter, Dr. Pepper cupcakes, olive-cream cheese sandwiches, cheese-wrapped pickles, kimchi grilled cheese. There were plenty of viral pasta mashups, some good (creamy miso pasta) and some not so good (lasagna soup). One mashup from that era, which I actually really enjoyed, was One-Pot French Onion Pasta (recipe below).

I have a thing for onion pastas in general. For example, I am obsessed with a very simple recipe for bucatini alle cipolle. Well, it isn’t really much of a recipe:

Thinly slice six yellow onions. In a saucepan or pot, cover them in olive oil, and cook gently over low heat, being sure to keep an eye on them and stirring often. Be patient. After about 35-45 minutes (or more), when the onions are very soft but still hold their shape, you cook the bucatini, drain, and then toss the pasta with butter, a “generous amount” of Parmigiano, and then add onions. Serve with a “generous amount” of ground black pepper.

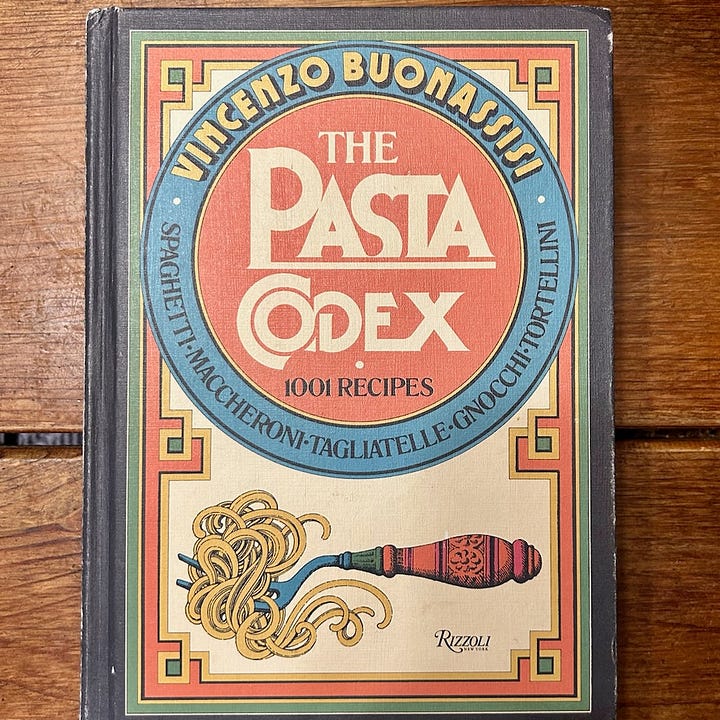

I got this recipe for bucatini with onions from Vincenzo Buonassisi’s The Pasta Codex, his 1974 masterwork, finally translated into English in 2020. “Obviously this is a sauce for onion lovers only,” Buonassisi writes. “This dish takes rustic and simple ingredients and elevates them into a dish fit for royalty. It is truly fantastic.” I completely agree.

If you’re a pasta lover and you don’t know The Pasta Codex, you should get to know it. “Is it a vicious lie that pasta makes you fat?” Buonassisi asks in his introduction. He delves into who invented pasta (likely “primitive man”), explicates the Roman poet Horace’s beloved “tagliatelle” with leeks and chickpeas, dismisses the myth of Marco Polo bringing spaghetti from China, muses on the taste for sweet pastas during the Renaissance, and notes a document from 1041 in which the word maccherone is used to insult someone as “a bit of a dope.” We learn that the first forks were brought to Italy—to make pasta eating easier—from Byzantium in the late 11th century, that a 1792 American cookbook erroneously suggested pasta be cooked in water for three hours, and that Lord Byron “connected pasta with erotic themes” offering, in his Don Juan, an aphrodisiac of vermicelli, oysters, and eggs. As to whether pasta is unhealthy, Buonassisi dismisses the notion, insisting instead that pasta is “a way to rebel at the table against a lifestyle that oppresses humanity at every turn,” that a dish of spaghetti “can provide a pure and simple boost of optimism,” and that “pasta remains a good friend to all.”

And this is all just in the first dozen pages. What follows then are 1,001 recipes, beginning with a simple spaghetti aglio e olio and ending with maccheroncini col ragu di cammello (“Camel is featured on the table frequently in Africa, but you must seek out a young camel—no more than three years old”). There are historic recipes, such as the 18th century Neopolitan dish thought to be the first pasta recipe that calls for tomatoes, a pasta with honey dating to the Middle Ages called sucamele (“honey-suckers”), and an ancient Florentine chickpea pasta dish, strisce con i ceci. There are curious regional variations, such as buckwheat noodles from Valtellina in the Alps, gnocchi from Trieste stuffed with plums or apricots, and knödel from German-speaking Alto Adige. There are even appearances by non-Italian “pastas” such as spätzle, pierogi, kreplach, and tagliatelle cinesi (ie. Chinese noodles).

All of which is to say that The Pasta Codex might be one of the most delightful cookbooks I’ve ever come across. It was a labor of love for Buonassisi and the capstone of a career that includes many years as a food and wine correspondent for Corriere della Sera and La Stampa, as well as the host of numerous cooking shows on Italian television. He died in 2004, long before seeing his work translated into English.

Given the context of this post, perhaps we can call Buonassisi’s The Pasta Codex what it really is: the Kama Sutra of pasta.

Recipes: Four Pastas of Passion

Recipes are for paid subscribers only. Upgrade today!