Wine and the Sweet Hereafter

One of my favorite pieces of wine and travel writing began with a used book from 1956 that I bought at a local library sale.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that umlauts scare away American wine lovers. For whatever reason, bottles with labels bearing those diacritical points, floating above terms like spätlese or grapes called spätburgunder or müller-thurgau or places named Würzburg or Württemberg, are a turnoff for so many English-speaking consumers. Let it be said, then, that I am somewhat out of step with my fellow Americans. Though I speak almost no German, I love wines with umlauts. And I go to significant lengths to seek them out.

That’s why on a balmy, blue-sky morning in late spring, I found myself in a western German village called Piesport, which sits at an S-shaped bend in the Mosel River. As the river gently meandered beside me, I gazed straight up at an imposing hillside vineyard called Goldtröpfchen. This vineyard is incredibly steep, with an incline in parts of more than 60 degrees—so precipitous and treacherous that there are small monorails snaking uphill, where workers can load harvested grapes into mechanical cars rather than risk hauling them down to the bottom.

I could walk only a little ways up the incline, crunching the brittle blue-slate soil under my shoes; I slipped slightly as I stepped. Kai Hausen, the young winemaker I walked with, chuckled. “The best wines always come from the most difficult vineyards,” said Hausen, who works nearby at Nik Weis St. Urbans-Hof, which owns about three hectares of this vineyard.

Goldtröpfchen means “droplets of gold,” referring to the wine that’s been pressed from the grapes grown here—and prized—for centuries. The 4th-century Roman poet Ausonius celebrated this vineyard in his poem “Mosella” (“River whose ridges are crowned with the vine’s odoriferous clusters!”) and a Roman wine press from the same era was unearthed at the foot of Goldtröpfchen in the 1980s. It was in the 18th century, so the story goes, that a Lutheran pastor persuaded the local farmers to plant only riesling. As you enter the town of Piesport there’s a sculpture of a vine with a drop of gold that reads, “Heimat des Goldtröpfchen.” The sign means “home of the golden droplets.”

Given the importance of such a vineyard, it’s fairly open to the public and well marked. People ride bikes, hike and picnic along trails rising from the river. Hausen and I lingered a bit in the cool breeze by the Mosel, watching a barge glide silently past. It’s so quiet and idyllic. “This is my favorite place,” Hausen said. As we headed back to the village center, I stared at the huge Hollywood-style sign that reads “Piesporter Goldtröpfchen” and realized why wine bottles bearing those words do not fly off the shelves back home.

A few hours later, I was still thinking about droplets of gold in the tasting room of another winery in Piesport, Weingut Reinhold Haart. The Haart family has been making wines since 1337, and I met Johannes Haart, in his late 30s, who’d taken over from his father several years ago. We tasted Haart’s beautiful rieslings, some of which have a touch of sweetness, something that the greatest old-school wines from the Mosel region are known for—often necessary to balance riesling’s characteristic tart, piercing (sometimes tooth-enamel-stripping) acidity. “With this style, I’m continuing what my father did,” Haart said.

Perhaps even more than umlauts, this reputation for sweetness is why many people don’t drink traditional German riesling. Americans mostly gave up sweet German wines in the late 20th century, after the market was flooded with cheap, low-quality brands like Blue Nun and Black Tower. While plenty of people in the wine industry, sommeliers and critics advocate for German wines, that sweet perception lingers negatively for the average wine drinker. So many times I’ve tried pouring German rieslings for friends and family—ones that are technically dry—only to be told, after a single sip, “It’s too sweet.”

Haart poured me a delicious, transcendent riesling from the Goldtröpfchen vineyard that was completely dry (or trocken in German). This was quite different from his father’s style. “It’s actually strange to have a dry Goldtröpfchen, since those were always the great sweet wines,” Haart said, adding: “Climate change is causing a loss of the old, classic styles.”

Climate change is a topic you can’t avoid in Germany’s wine regions. Yet the strange thing is, the talk is not all negative. Several recent harvests, including 2018, have been excellent, and many believe a golden era of dry German wines is upon us. “In many ways, climate change has helped us,” Haart said. “I’m experimenting with where it’s taking us.”

Haart, like others, chose his words carefully. This situation is sensitive and a little bewildering. For centuries, Germany has been considered a cool-climate region where grapes struggled to gain ripeness, struggled to ferment and made low-alcohol wines with significant residual sugar. Now, with the world’s unpredictable weather, winemakers here find themselves harvesting earlier in the fall, with a higher volume of grapes, and making wine that’s higher in alcohol—and most important, drier. In some corners of the wine world, there are uncomfortable whispers that parts of Germany might soon challenge more well-known areas of Spain, Italy or France, which are getting hotter and hotter all the time. How long will it be before someone sunnily declares a German wine region to be “The New Tuscany”?

“We are the big winners from climate change,” one German wine journalist told the New York Times in 2019. “I know it’s disgusting to say, but it’s the truth.”

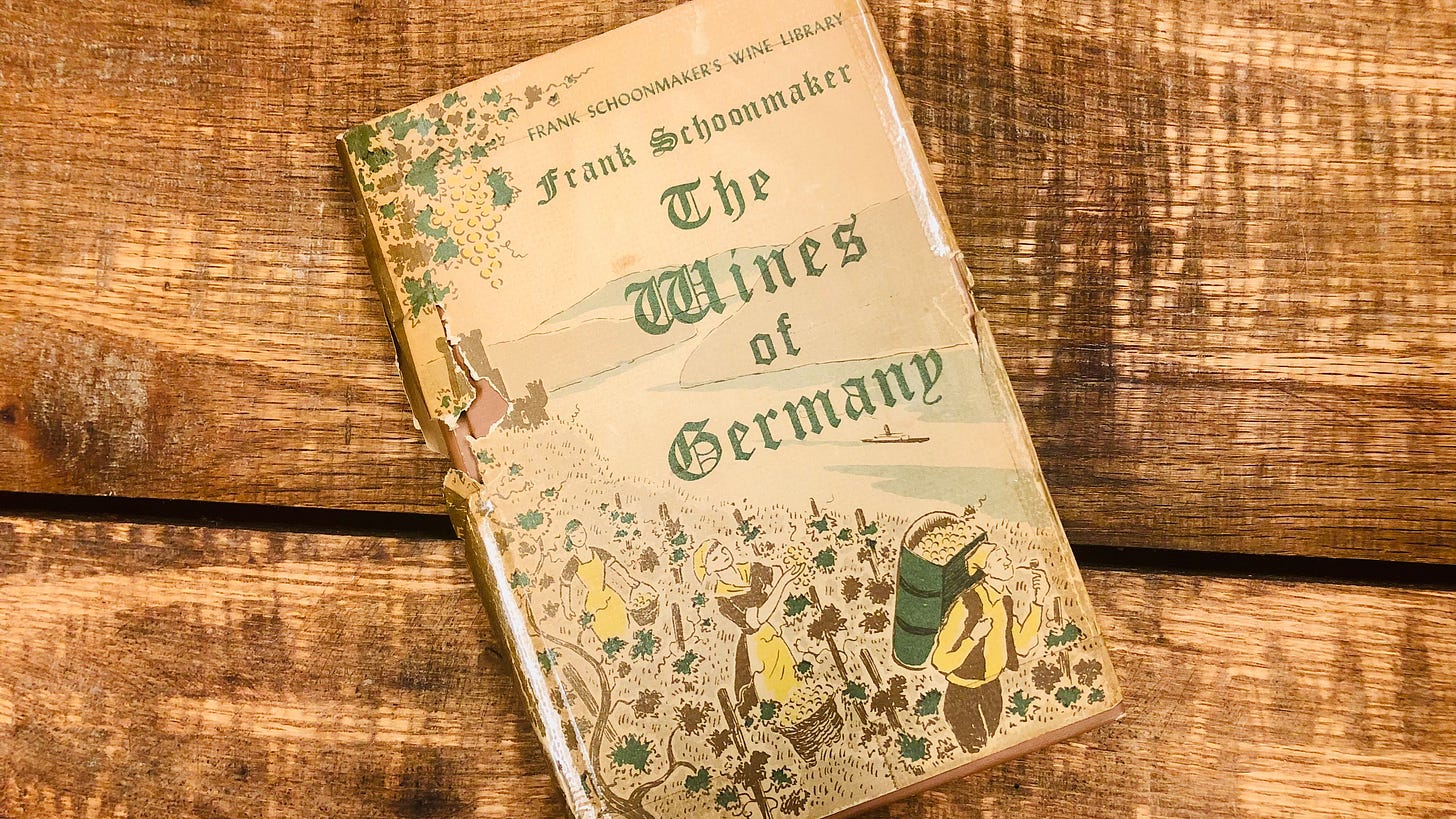

The journey that took me to Piesport, and Goldtröpfchen, began at a used-book sale run by the library in my small town in South Jersey. There, I found a weathered copy of a 1956 book titled The Wines of Germany, by Frank Schoonmaker, one of those bon vivant gentleman writers who flourished in the mid-20th century and among the first American wine journalists of note. Schoonmaker’s passion was for German wines, which was extremely complicated during that era.

In a 1946 issue of the New Yorker, he published a “Letter From Germany” on the Rhine wine country, reporting on the fate of the postwar vineyards. In that article, he noted that the American consumption of German wines “before 1914 was enormous” and reported that U.S. imports dropped from 2 million gallons in 1914 to about a half-million from 1934 to 1939. “Perhaps because of Hitler,” he speculated. Perhaps, indeed! Schoonmaker, with startling understatement, concluded: “It’s now possible that Americans, remembering the war, will have little taste for German wines.”

I paid my $2 donation for The Wines of Germany, took the book home, and started reading. It’s not bad, though the prose occasionally veers toward the purple: “Taste and smell are the beggars among our five senses—they have no true written language and therefore no standards other than wholly personal ones, and no permanent records and no past.” Still, Schoonmaker attempted to make the case for German wines at a time in postwar America when they were surely out of fashion. “Tasting a superlative Moselle,” he wrote, “can be an aesthetic experience no less genuine than hearing a Mozart concerto well played, or seeing for the first time one of Breughel’s paintings.”

But for me the greater value of the book was what I found stuffed between the pages. Throughout, there were handwritten notes, newspaper clippings, and even a notice from the 1980s of a lecture by a local lawyer on German wines. From these I pieced together that the book had been owned by a man who’d lived in my town, and it had become the de facto journal of his own wine journey. There was a printed menu from a special wine dinner, with wines from the Rhine and the Mosel, held at a house not far from mine in 1952. The one thing I couldn’t find was the man’s first name; I could find only the family name: Schmidt.

One of the most fascinating artifacts I found in the pages were a few dozen yellowing labels taken from wine bottles, many of them Piesporter Goldtröpfchen from the 1970s, and most from a winemaker named Edgar Welter in Piesport. I had never heard of this winery, and after emailing several of my wine contacts, I determined that the winery no longer existed. However, if Edgar Welter had owned vineyards in Goldtröpfchen, surely the vineyards themselves still existed. I wanted to find them.

I didn’t exactly know why this all mattered to me or had evoked such emotional connection. It seemed likely that the man was now deceased. I guess I felt a kindred spirit to this old wine hobbyist from another generation. Like me, he clearly had a passion for unpopular wines—so unpopular that all his German wine memories had been tossed onto the $2 table at a used-book sale. Since I was the one who had come into ownership of this book, I felt more than just gee-whiz curiosity. I felt responsible.

A visit to Germany’s wine country doesn’t have to be burdened by history. On the contrary, there is so much youthful energy in the wine scene, with so many experimental and enterprising young producers, that it always surprises me how few wine lovers visit. That energy is in stark contrast to the typical tourists here, an older crowd that floats down the Rhine on golden-years river cruises.

On my visits, I stay in the city of Mainz, less than a half-hour from Frankfurt’s airport. Mainz, considered one of the world’s “wine capitals,” is well situated for visiting wineries in both the Rheingau and Rheinhessen, two distinct regions on opposite sides of the Rhine. The city’s living history runs deep, with an old town of half-timbered homes, medieval squares and a 10th-century red sandstone Romanesque cathedral, as well as a museum for Johannes Gutenberg, who invented the printing press here in the 15th century.

In contrast to the past is a vibrant bar and restaurant scene, and a buzzing university community of more than 35,000 students that creates a fun, relaxed vibe. Mainz is a city that goes against the stereotype of Germany as a beer-drinking and sausage-eating nation. At a popular wine bar called Laurenz, my server, from a different region of Germany, told me, “When I moved here, I couldn’t believe how much wine that people were drinking here all the time.”

Just a few miles south lies Rheinhessen wine country, full of undulating green terrain dubbed “land of the thousand hills” and dotted by sleepy, beautiful villages, populated by small wineries and wine taverns. About a decade ago here, a number of young winemakers banded together to form a group called Message in a Bottle, determined to change the image of both Rheinhessen and German wines. That kind of energy would have been unthinkable 20 years ago, when the area was known as the home of Blue Nun and other cheap-and-sweet Liebfrauenmilch (“Milk of Our Lady”), a wine named after the Liebfrauenstift monastery in the city of Worms.

“A lot of young winemakers opened their eyes and saw the potential in the region,” said Stefan Winter, in his late 30s, who took over his family’s Weingut Winter in the sleepy village of Dittelsheim in 2000.

“We had a really bad image here,” said Marc Weinreich, whose family runs Weingut Weinreich in Bechtheim — a village of only 1,800 people, though with more than 30 wineries. It was sunny and warm during my visit, and Weinreich poured his wines outside in the courtyard, next to their small guesthouse that rents rooms to wine tourists. “The last five to 10 years have been very exciting in Rheinhessen, lots of good new ideas,” said Weinreich, who took over the winery with his brother when their father died in 2009, and converted to organic farming. Like a lot of winemakers in Rheinhessen, Weinreich quickly broke from tradition to focus on dry wines. “In the past, we had a lot of sweet wines on the list. Now we only have one sweet wine,” he said.

His neighbor in Bechtheim, Jochen Dreissigacker, also took over his family’s traditional winery not too long ago, built a sleek new winery and also changed to organic growing. “Everything we do is for the future. We all know it will keep getting warmer and warmer,” Dreissigacker said. Still, modernizing doesn’t mean tossing aside centuries of tradition. “We have something so special here with riesling. It’s one of the only white wines in the world that can age, that you can store in your cellar and then open many years later,” said Dreissigacker. Those extra years of age allow riesling’s searing acidity to mellow and the flavors to evolve and become more complex.

This need to be patient and let good riesling age is, of course, probably another reason it often baffles Americans. The majority of wine in the United States is uncorked and drunk on the day of purchase.

Rheinhessen stands in contrast to the Rheingau, the famed wine area on the other side of the Rhine, home to Germany’s most historic vineyard area. The wines from here (alongside those from the Mosel) were the ones that excited Schoonmaker back in the mid-20th century: “There are other sections of this incomparable Rhine Valley which are perhaps more impressive than the Rheingau, but none, surely, more gracious and more beautiful.”

Here in the Rheingau, the experienced wine traveler is more likely to find the sort of bustling touristy tasting rooms they’re accustomed to—though the best, such as Weingut Robert Weil, Weingut Peter Jakob Kühn, and Weingut Künstler, are still wonderful. Among my favorites of the next generation is Eva Fricke, who started her winery at 28 and is now in her early 40s. Fricke farms organically and seeks to reinterpret the grand tradition of the Rheingau that Schoonmaker and his contemporaries would have loved. “For the first time in 40 years, we’re seeing an uptick in quality and purity in the wines from Rheingau,” Fricke told me in her quiet, stylishly simple tasting room.

Down the river, above the town of Oestrich-Winkel, stands Schloss Vollrads, a lovely castle where wine has been made for at least 800 years. In his book, Schoonmaker raves about sipping Schloss Vollrads’ 1920, 1945 and 1953 vintages. (His tasting notes: “All were above criticism and beyond praise.”) A few minutes away is Schloss Johannisberg, a castle that sits on the spot where the ruler Charlemagne is supposed to have ordered the planting of vines in 817. According to legend, Charlemagne lived across the river, in Ingelheim, and noticed each year that the snow there always melted first, and thus made his decree.

I visited the vineyards of Weingut Leitz, surrounding the town of Rüdesheim, rising almost a thousand feet above the Rhine. Many of the river cruises dock at Rüdesheim, so there are plenty of tourists, some taking in the view by riding cable cars that climb above the vines.

Johannes Leitz’s father founded the estate in 1947, just a few years after Rüdesheim was destroyed by Allied bombing. “When I was growing up in the 1970s, there were still a lot of ruined houses,” Leitz said. His father died in the 1960s when he was a baby, and his mother kept the winery going while also running a flower shop until Johannes was old enough to take over in the 1980s. “When I started,” said Leitz, “there was no future in wine.”

Rüdesheim has several of the most coveted vineyard sites in Germany, and we explored the 60-degree steep slopes where Leitz tended his vines, bearing names like Drachenstein (“Dragonstone”) and Kaisersteinfels (“Kaiser Stone Rock”), Rosengarten and Roseneck. In the distance, Leitz pointed out the abbey of St. Hildegard von Bingen, the mystic 12th-century Christian nun who wrote many books and plays, composed haunting hymns still sung today and wrote early texts on natural history (including commentary on wine).

Later, as we tasted Leitz’s exquisite rieslings, he bemoaned the state of German riesling in America. “I’ve been coming to the U.S. since 1991, and they still say, ‘I can’t sell riesling,’ ” Leitz said. “Everyone loves riesling once it’s in the glass, but few will order it.”

Fricke, who was mentored by Leitz and managed his estate for many years before blazing off on her own, said she was putting her faith in the younger generation someday embracing riesling like theirs. “There’s a completely different style of drinking than even 10 years ago,” she said. “The old wine customer, the one who thought a certain way about these wines, is dying out.”

It was a few days later when I ended up in the Mosel Valley, in the village of Piesport. Nik Weis, the owner of St. Urbans-Hof, had helped me track down Edgar Welter, the name of the winemaker whose labels I’d found in The Wines of Germany. I was told that Edgar was an old man now and that his son had married into another winemaking family. His vines in Goldtröpfchen were now owned by the winery Später-Veit, just down the road from Haart.

I was unsure if Edgar, at 82, would be up for a visit, and so I met Edgar’s 27-year-old grandson, Niklas Welter, who is the winemaker at Später-Veit. While a leather-clad group of middle-aged motorcyclists from the Netherlands finished up lunch at the family’s riverside restaurant, Niklas poured several of the more recent Später-Veit wines, including a 2015 Piesporter Goldtröpfchen. It was very dry, and I asked Niklas if he saw this as a new style. “No,” he said. “This is the real old style, going back 80 years, before the war. Then it was dry. The style only became sweet after the war.”

I showed Niklas the labels from his grandfather’s old wines, and he looked at them in quiet confusion, seemingly unsure what to make of this strange visitor asking about wines made two decades before he was born. Then suddenly, he said, “Why don’t I bring my grandfather over, and maybe we can taste some of these wines.”

Within an hour, Niklas returned with his brother, Eric, and their grandfather Edgar, along with a few dusty old bottles in tow. Edgar knew immediately who’d owned the used book I’d bought. “That’s Mitchell’s! He was my best friend and he became my best customer! For about 20 years, he used to visit us here every other year.” Edgar confirmed, sadly, that his friend Mitchell had died several years ago. But the mood was mostly one of happiness, and Edgar spoke excitedly and quickly. The look of surprise on his grandsons’ faces made me wonder if they’d ever heard him speaking English before. Edgar told me that he’d visited my small town in suburban New Jersey several times. “You did, too, when you were a baby,” he told Niklas. “Don’t you remember?”

Apparently, Mitchell had first turned up at Weingut Edgar Welter in 1970. Edgar didn’t speak any English then, but he understood that Mitchell had come to Piesport to see why his own father had collected so many bottles of Piesporter Goldtröpfchen in his cellar that dated to before the war. Edgar and Mitchell tasted wines from the barrel and struck up a friendship. “Until then, I felt there was nothing special about being a vintner. It’s a hard, thankless job, but just a job,” Edgar told me. “But then here’s a fellow from the U.S. who took the time to come over here and take an interest in my work. I began to view my profession differently. It changed my life.” Soon after, Edgar decided to learn English and traveled abroad for the first time.

Niklas and Edgar opened some old Piesporter wines from 1986, 1982 and 1969. The 1969 would have been the same wine that Edgar tasted with his old friend on that first visit in 1970. The 50-year-old riesling was still incredibly alive and kicking. “I can’t believe this wine is still drinkable!” exclaimed Edgar. “It may not be the quality that it once was. But it’s sort of like an older lady who you can tell was a great beauty 30 years ago.”

We sipped some more, silently. Then Edgar exclaimed, “You cannot imagine how lucky I feel today! To get to taste these wines and to think about my old friend. I didn’t know if I’d ever taste this wine again before I died.” He was so overwhelmed that tears welled up in his eyes. “This is a special day, but there’s also some sadness in all this happiness, too.” Even though I was mostly a bystander to everything that was happening, as I tasted this wine—a year older than me—I’ll admit to being overwhelmed, too. I didn’t want to overstay my welcome, and so after about an hour, I bid Edgar and his grandsons farewell.

As I left the Welters in Piesport that afternoon, I thought hard about how profound the overlapping layers of wine can be. In 1970, Mitchell, a guy from my hometown, visited Piesport to learn why his father had loved the wines from Goldtröpfchen. Nearly five decades later, I arrived in Piesport and tasted those wines, along with Edgar’s grandsons, who were now responsible for those same hillside vines. For perhaps the last time, Edgar was able to revisit something he’d made as a young man, during the same era as when a visit from an American stranger had changed his life. And for me, I was able to share all this and, in some small way, be part of closing a circle.

Perhaps this is the reason, for thousands of years, humans have viewed wine as more than just a drink. It’s why the Roman poets waxed lyrical about it, why the medieval monks and nuns nurtured their grapes, why for centuries people have debated, decreed, and fought over which is the finest, and perhaps it’s why the New Yorker felt it was important enough to send a journalist to Germany in the aftermath of war to check on the state of its vineyards.

Wine certainly changes according to the fashions of the day, just like hemlines and lapel widths. Riesling becomes sweeter or drier, more or less popular. But wine also stays constant in ways that are deeply human. As the world’s climate changes, both literally and figuratively, it’s good to visit places that remind us of this.