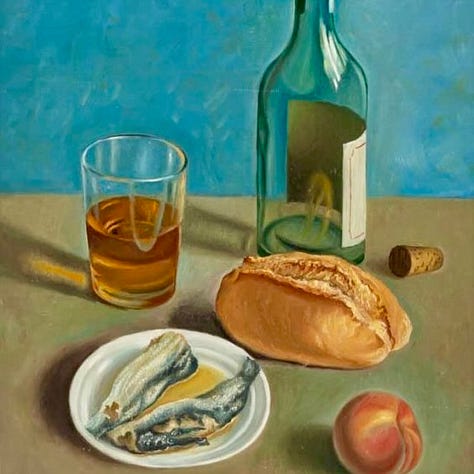

Still Life With Wine

Maybe posting your blurry bottle pics isn't so bad? In any case, you're part of a grand tradition.

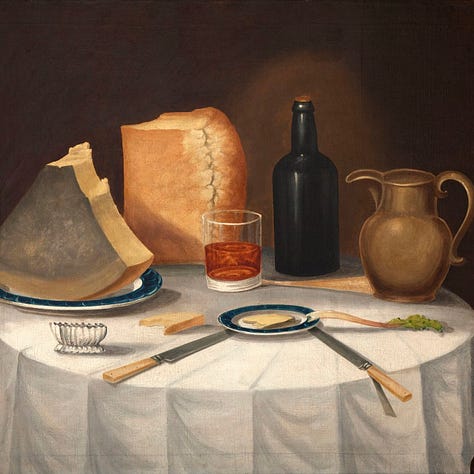

I love to look at still life painting. When I go to the world’s great art museums, I’ll often skip the grand masterpieces and head straight for a simple painting of objects on a table. I do sometimes enjoy the ostentatious, over-the-top still life of the Dutch Golden Age—the so-called pronkstilleven, showy tables overflowing with shellfish, exotic fruit…