In Praise of the Other Pinot. The White One.

You can call it pinot blanc, pinot bianco, or weissburgunder. And you can decide for yourself how it pairs with this strange recipe for blueberry risotto.

Purple food, for most people, is weird. But one afternoon I was served a curious violet-hued plate of a risotto, made with fresh blueberries, at a restaurant in the Italian Alpine region of Alto Adige. My encounter with purple risotto ai mirtilli was not exactly love at first bite, but with each forkful, as I wrapped my brain around the incongruous—yet, in the end, savory—flavors, my affection grew. Before I was halfway finished, my thoughts drifted away from the table. I was having a double Proustian memory of both the ripe, mid-summer blueberries of my South Jersey childhood as well as my clumsy, study-abroad attempts to master the art of risotto-making, namely to impress a girl who remained woefully unimpressed. (Paid subscribers can read my story on uncovering the truth about blueberry risotto below the paywall).

Blueberry risotto might be a strange dish upon which to have a madeleine moment. But then Alto Adige is a peculiar place, a corner of Italy where a majority of the locals speak German, and call the area Südtirol (or South Tyrol) and not Alto Adige. The town where I was eating the risotto ai mirtilli, Appiano, would be called Eppan by the German speakers of South Tyrol. In fact, those who identify as South Tyroleans still feel a bit of nostalgia for the Austrian Empire, to which they belonged until the empire collapsed after its defeat in World War I. An ambivalence, even hostility, to Italian ways lingers in Südtirol, dating to Mussolini’s fascist program of Italianization, banning German language and culture, which one can imagine proved extremely unpopular here.

During that lunch of blueberry risotto, I was tasting wines with an export manager for the winemaking cooperative in the village of Colterenzio—or Schreckbichl (“scary hill”) if you prefer the German. “I hope you realize how different Alto Adige is from the rest of Italy,” she said, as we ate our purple rice.

In particular we tasted pinot blanc. The export manager proselytized the wonders of this grape, which is alternatively pinot bianco or weissburgunder, depending on your language. “My mission has been to have pinot bianco become the next pinot grigio in the U.S.,” she told me. “Many people are getting sick of hearing about pinot grigio. I mean, come on. It’s been going on for how long?” (Wine nerd note: all of the pinots—pinot noir (black), blanc (white), and gris (grey)—are mutations from a single variety.)

Pinot blanc is the everyday wine of Alto Adige—if you ask for a white wine there in a bar, you’ll most likely be served a weissburgunder. The grape was brought to the region in the 1850s by the Austrians. “Alto Adige was the main producer for the monarchs in Vienna,” I was told by the export manager at another village cooperative, Cantina Terlano (or Terlan in German).

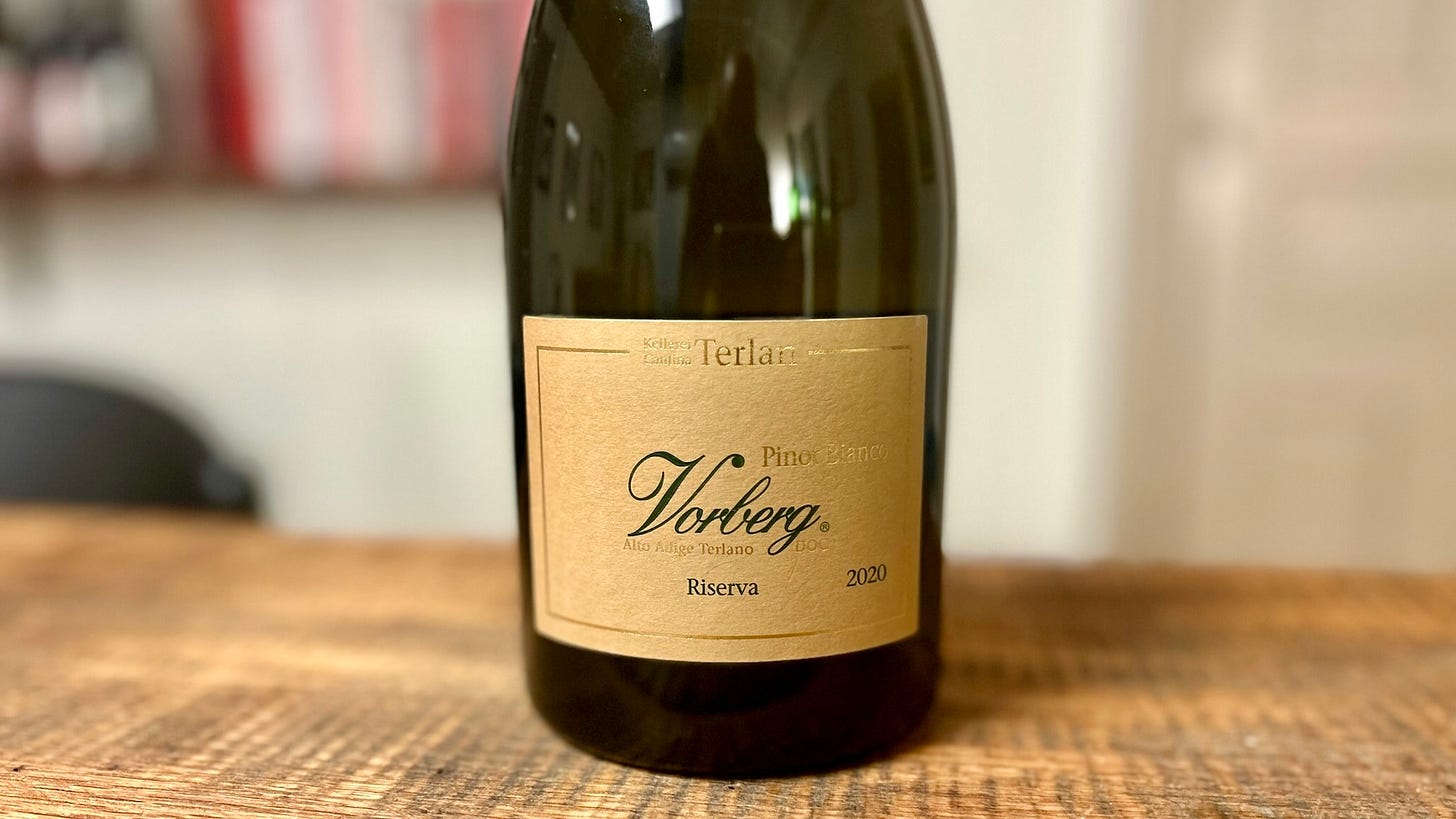

Many believe that pinot blanc has great aging potential, and it’s hard to disagree when I taste a bottle like Cantina Terlano’s Vorberg Riserva—consistently one of my favorite white wines in the world. I’ve tasted older vintages of this wine, including a deep, nutty 2002 that could have easily been mistaken for aged Burgundy.

Of recent vintages, both the 2020 and 2021 Cantina Terlano Vorberg Riserva are amazing. They’re both such pretty, elegant wines, which open with a fresh nose of herbs and evergreen forest and then turns toward honey and white blossoms. But on the palate, they’re opulent and ripe—a fruit basket of pineapple, melon, apricot, and pear—balanced by great acidity and a long mineral finish. 2021 is slightly crisper and lighter, the 2020 a little more heft, but both have a long life ahead of them. It’s incredible that a benchmark wine like this can still be found for under $45.

I believe the finest expressions of pinot blanc usually come from the German-speaking world. For instance, another benchmark for me is from Christian Tschida, one of my favorite Austrian winemakers. Tschida’s All the Love of the Universe is a vibrant and elegant weissburgunder that comes from a single vineyard of the chalky soils in Burgenland’s Neusiedlersee region.

And then there is the pinot blanc from Germany’s Pfalz region. A couple of years ago, I wrote about a dinner in Schweigen, along the French-German border, at Weinstube Jülg. There, I drank beautiful weissburgunder along with the winemakers from Jülg, Friedrich Becker, and Bernhart. Rather than blueberry risotto, we ate delicious escargots as a perfect pairing

I think weissburgunder can offer a new path into German wines for people— perhaps that committed chardonnay drinker—who may not appreciate riesling. “What’s charming about pinot blanc is it ages harmoniously, and it’s not polarizing,” said Franz Wehrheim of Dr. Wehrheim. Pinot blanc can be crisp, refreshing, and great value, but at the top end it can also be intense, deep, and full of minerality.

I still think about a certain pinot blanc from that trip: Weingut Kranz’s excellent 2020 Kalmit GG Weissburgunder, and even more so about their 2014 Kalmit GG Weissburgunder, which had everything—rich, fruity, herbal, tropical, with notes of candlewax, strawberry, nectarine, Earl Grey tea, with lively acidity, and an incredible salty finish. It demonstrated pinot blanc’s amazing potential.

There are more good-value pinot blanc recommendations below (all under $30). Also below is my story of uncovering the truth about blueberry risotto, and a recipe! All for paid subscribers—upgrade today!