How Will Jura Survive The Climate Crisis?

The tiny French region, darling of sommeliers everywhere, sees its future in local grapes savagnin and trousseau. Plus: 17 bottle recommendations and tasting notes.

Driving into the Jura, heading north and east on France’s N83 toward Arbois, I took in the sight of rolling green hills, woodlands, red wildflowers by the roadside, and quaint little villages. The landscape was patterned with vineyards, fields of grain, and meadows dotted with grazing cattle. In a town with a single stop sign I passed a farmer leading his horse by the reins down the road. Situated in the foothills of the Alps on the border with Switzerland, the Jura looks a lot like the Shire—just populated by French humans rather than Tolkien’s hobbits.

On the winding route between the villages of Poligny and Arbois, I passed a small whitewashed structure by the road that had the words SAVAGNIN POWER and a raised fist stenciled in black on its wall. It strikes a defiant and hopeful note in a wine region that, perhaps more than any other in France, has been roiled by climate change. It’s savagnin, Jura’s ancient white grape, that might be the answer to the crisis here, but it’s a complicated story.

Arriving in Arbois, I checked into La Closerie des Capucines, a 17th-century manse converted into a five-room guesthouse, owned and recently renovated by wine importer Neal Rosenthal. After a warm welcome from the hotel’s manager, Elise Vincent, I was primed to enjoy some local wines. From the honor bar I poured a glass of Michel Gahier's “La Fauquette” melon à queue rouge (a local strain of chardonnay, and the subject of much debate over whether it’s a distinct variety) and sat on the terrace in the garden.

A church bell tolled out the late afternoon hour to the town’s population of 3,100 people. Bees hummed in the sunshine of a 90-degree late-June day over heady jasmine blooms and harmonized with the sound of the River Cuisance burbling behind the guesthouse. The wine was rich and elegant, with dense citrus fruit, some oxidative notes, and a saline finish. Maybe the beauty of the place (not to mention my jetlag) was making me soft and falling in love with everything at that moment, but I wondered if the wines I’d be tasting in the following days could possibly get any more “Jura” than this chardonnay (which is what I’m choosing to call this melon à queue rouge mutation).

Over the past 15 years or so, the Jura has become a bit of a fetish among somms and the natural wine crowd for its “weird” wines. While wines made from red ploussard and trousseau grapes were early darlings, so too was the Jura’s distinctive vin jaune—the traditional, inimitable “yellow wine” that's aged under flor (or sou voile, “under the veil”) and shares similarities with sherry, though it's unfortified—and later its ouillé white wines, non-oxidative wines topped up in barrel (ouillé means “full”), Burgundian style, often made with organically grown grapes and low-intervention winemaking. Then there are the in-between white wines that might spend some time sous voile, though not the minimum of five years to qualify as vin jaune. At any rate for most American wine drinkers, these wines have remained rather off-piste, if intriguing.

The next morning, I met my guide from Mad Rose Journeys, a partner group of the guesthouse, and we drove out of Arbois. The Jura is a tiny wine region, the smallest in France, with just about 2,000 hectares of vineyards planted. It’s located due east across the Bressan plain from Burgundy, and in some ways it’s the mirror image of that region. The elevation is roughly that of the Côte d’Or, and the climate is similar, if a bit wetter. But while Burgundy largely faces east and is roughly 80 percent limestone with 20 percent marl and clay, the Jura is the obverse, mostly facing west with predominantly marl bedrock and approximately 20 percent limestone.

About 43 percent of vineyards in the Jura are planted with chardonnay, making it the most planted variety overall. Much of it goes into sparkling Crémant du Jura, but also white still wines that have become wildly popular as a delicious alternative (for both the palate and the pocketbook) to Burgundy whites.

When it comes to red grapes in the Jura, ploussard (aka poulsard) is beloved for its pale, perfumed, ethereal reds—some of which are so light-bodied and pale in color that you might call it a rosé in a blind tasting. And while chardonnay and ploussard are the most-planted white and red varieties, that might change in the future: it’s the white savagnin and the underdog red trousseau that show the most promise in the face of climate change.

Pupillin, a town of just 200 people south of the town of Arbois, is the “World Capital of Ploussard,” as a sign on the main road (called, naturally, “Rue du Ploussard”) proudly declares. And in fact, ploussard is grown pretty much nowhere else in the world but here in the Jura. In the equally tiny village of Montigny-lès-Arsures, north of Arbois, you might not realize you’re in the “World Capital of Trousseau” except for the odd mention of it on a sign for EAU POTABLE above a public drinking fountain by the town church.

Here in Montigny, Marin Fumey is the second-generation winemaker at his family’s domaine, Fumey-Chatelain. He studied winemaking in Burgundy, and worked abroad at wineries in Australia (Spinifex Wines), South Africa (Alheit), and New Zealand (Burn Cottage). He helped lead the family domaine to organic certification, with conversion to biodynamics planned for the near future.

Fumey drove me to one of his vineyards planted with trousseau, which he bottles in a cuvée called Le Bastard as a nod to the variety’s name in Portugal (where it’s grown and known as “bastardo”). He pulled down the branch of a cherry tree and offered ripe fruit to snack on while we walked through the vines. Trousseau is thick-skinned and vigorous, and needs a warm site like this one to ripen—an advantage in the Jura as hot and dry growing seasons become more frequent here. Ploussard, meanwhile, is early ripening and thin-skinned, prone to rot and sunburn. All these things make it highly susceptible to the perils of climate change: damage from spring frosts, disease pressure in wet weather, and hot, dry weather in the growing season.

“Ploussard is definitely the one that suffers the most here,” Fumey lamented. “In 2022, for example, we had a good harvest and good yields in general, but we lost about 80 percent of our ploussard because of sunburn.”

Fumey drove us down twisting roads to another vineyard site, and slowed the truck so we could admire a herd of Montebéliarde cows, the red-and-white breed used to produce the famed local Comté cheese, as they grazed in a pasture at the foot of a vineyard. “Even if they’re not your cows, they are often around the vineyard, and it's nice to have animals close to the vines,” he said, to increase biodiversity in the growing environment.

Fumey-Chatelain recently planted new vines in an old cow field in Grevillière, on a plot that the domaine purchased and split with Marin’s father’s cousin Stéphane Tissot. Much of the new vineyard is planted to trousseau, which Fumey admitted is his favorite variety. “Trousseau is super playful. It's good underripe, it’s good overripe, and it’s good when it’s perfect,” he said.

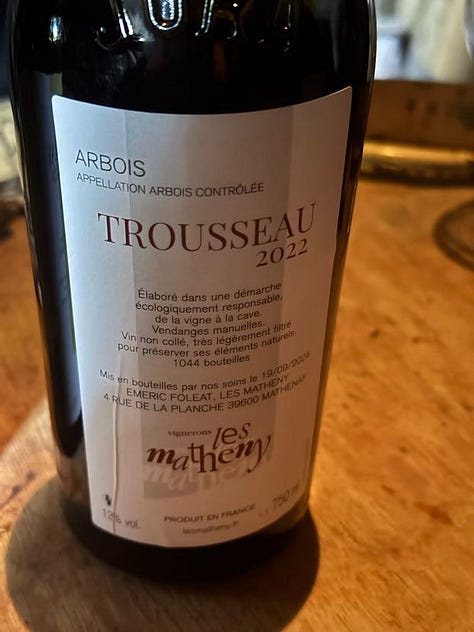

When it comes to small, artisan producers in the Jura, you might be hard-pressed to find someone who fits the description as perfectly as Emeric Foléat, owner of Vignerons Les Matheny. Foléat worked under the legendary winemaker Jacques Puffeney for years before launching his own one-man winery. You won’t find him on Instagram or Facebook, nor does he have a website. He’s busy tending to his small holdings—just four hectares of vines—and making wine in the low-tech cool of his small cellar in Mathanay. We joined him in his cellar to talk and taste his wines, and when he couldn’t find his spittoons, he urged us to aim at the cellar drains instead. “Pour les souris!” he joked. “For the mice” to taste.

Although Foléat says he loves the challenge of growing ploussard, he also has half a hectare of trousseau. The cuvée I tasted was dark-fruited, spicy, and broad, but elegant. It’s a totally unique expression of trousseau—and it underscores how this variety is capable of myriad iterations.

It’s another local variety, savagnin, that grape growers are pinning their hopes on in the Jura. Savagnin's history here runs deep. Since the 13th century, it’s been used to make vin jaune, and much more recently, ouillé wines. It thrives on the rich marl soils of the Jura. It’s thick-skinned and thus has good disease resistance. And whereas chardonnay can lose acidity quickly with a rise in alcohol, savagnin manages to retain it.

“Savagnin is really good with the hot vintages, because it keeps quite a lot of acidity even when it's high in alcohol. It keeps a lot of freshness,” Fumey explained as we drove by a plot of the domaine’s old savagnin vines that were planted when Marin’s grandmother was born, 90 years ago.

In L’Étoile, the smallest appellation in the Jura, 90 percent of the vines planted are chardonnay. L’Étoile (meaning “the star” in French) is supposedly named after either the formation that the appellation’s five villages make in relation to each other, or the distinctive fossils found in the limestone-rich soils here. At Domaine de Montbourgeau, I became firmly convinced that the name comes from the latter explanation when I peered into a small plastic tray of what looked like bullets and perfectly star-shaped beads: belemnites and crinoids, squid- and plant-like marine fossils from the Jurassic era found in the soils of L’Étoile.

Domaine de Montbourgeau is a 10-hectare estate, mainly planted with chardonnay and savagnin. César Dériaux took over the role of winemaker—with his brother overseeing the vineyards—from his mother in 2019. Above their plot of savagnin called Les Budes, Dériaux told me that while their chardonnay vines are now struggling with acidity and alcohol levels as average temperatures increase, savagnin is performing better, as it ripens later. He said that he is loyal to chardonnay, as it’s traditionally been planted in L’Etoile, but they replace chardonnay vines on the domaine that need replanting with savagnin. He also explained that while savagnin does have an affinity for marl, it actually works with all soil types in the Jura.

Savagnin and trousseau are weathering climate change well, but the vagaries of the market are another story. “In terms of sales, it’s easier to sell a chardonnay than a savagnin,” said Fumey. For most consumers, “if you can get them to drink Jura, that’s already cool, but if they have to choose between a chardonnay and a savagnin they’ll go for the chardonnay. They've never heard about savagnin, they mistake it for sauvignon blanc.”

Chardonnay and ploussard certainly aren’t going to disappear; they’ve been cultivated in the Jura for centuries. Dériaux noted that the challenges for chardonnay can be answered with early harvesting and adjustments in the cellar to retain acidity—but it will require more work. And as Fumey explained, growers are also using massale selection to cultivate vines that can better withstand climate change (including the local melon à queue rouge mutation).

But in the meantime, climate change continues to rock Jura’s grape growers. Mercifully, the 2025 growing season has thus far been uneventful, but Foléat enumerated all the challenges that vignerons in the region have faced in the last few years: catastrophic spring frosts in 2017, rain and hail in 2021, drought in 2022. The 2024 vintage was particularly devastating for the Jura, with a trifecta of severe frosts, wet weather, and hail. Last year, Foléat was able to harvest only a third of his crop. But this growing season reminded some of the Jura vignerons I spoke with of the 2020 vintage, when the growing season was warm but the grapes were healthy.

Later that night, after a long day of talking and tasting, I sat on the terrace overlooking the river at Restaurant Les Caudalies in Arbois, eating the classic local dish of braised chicken with morels in a creamy vin jaune sauce—paired with a Domaine de Montbourgeau chardonnay that spent time sous voile—and marveling at the singularity of this place and its wines.

Savagnin and trousseau vines might be popping up in places like Australia and Oregon, but their identity is riveted to the Jura. As these two varieties take a more prominent role in the region, it’s exciting to imagine the wines that will emerge. Especially savagnin, as it is capable of such diverse styles, from vin jaune to ouillé wines and even skin-contact. The savagnins I tasted had such remarkable acidity and freshness, texture, unique aromas and flavors, and always with the trademark minerality of the Jura. And they are wines with incredible potential to age in bottle. Trousseau, meanwhile, makes wines that are almost a contradiction—light-bodied, lifted, but with serious weight, structure, and a dark-fruited, woodsy, gamey profile that is immediately enjoyable but ageworthy, too.

Below are the tasting notes from my recent trip, including savagnin, chardonnay, trousseau, and ploussard (and blends!). As ever these days, some of these wines might be increasingly difficult to find, given the ongoing idiotic situation with tariffs, and some of the latest vintages haven’t yet arrived in the U.S., but they’re worth the effort of tracking down, or waiting for.

17 Wines For Jura Jammin’

Bottle recommendations and tasting notes are for paid subscribers only. Upgrade today!