How Things Disappear: A Travel Writer's Pilgrimage

On tough editorial calls, Rick Steves, and a small town in Andalusia.

In this terrible age of media—when we are told that travel writing is dead or dying—I made a travel writer’s pilgrimage, winding through miles of olive-tree forests in Andalusia’s interior, to the small hilltop town of Estepa. I’m still not exactly sure why.

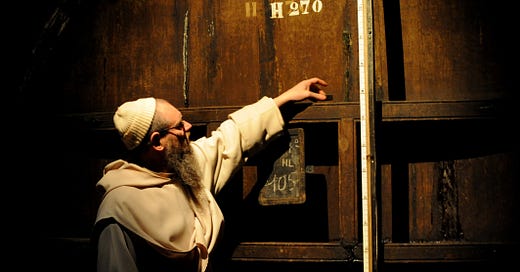

Estepa is a relatively random town situated between the bigger cities of Córdoba and Málaga in southern Spain. I was in Córdoba on assignment, and I’d had a Saturday morning appointment with a winemaker in Montilla, a guy who made strange, dry wines in this hot climate from the Pedro Ximenez grape.

After the meeting, in the bar of an old restaurant in Montilla, I ate a big, carnivorous lunch alone. As a group of men argued over glasses of the local wine, I ate a plate of paper-thin jamón Ibérico de bellota, followed by grilled pluma Ibérico, washed down with a half-bottle of an oaky tempranillo. After lunch, I had a free afternoon and no one awaiting me in Córdoba, so I decided to drive another hour further south, through a series of bright, white-washed villages, to Estepa.

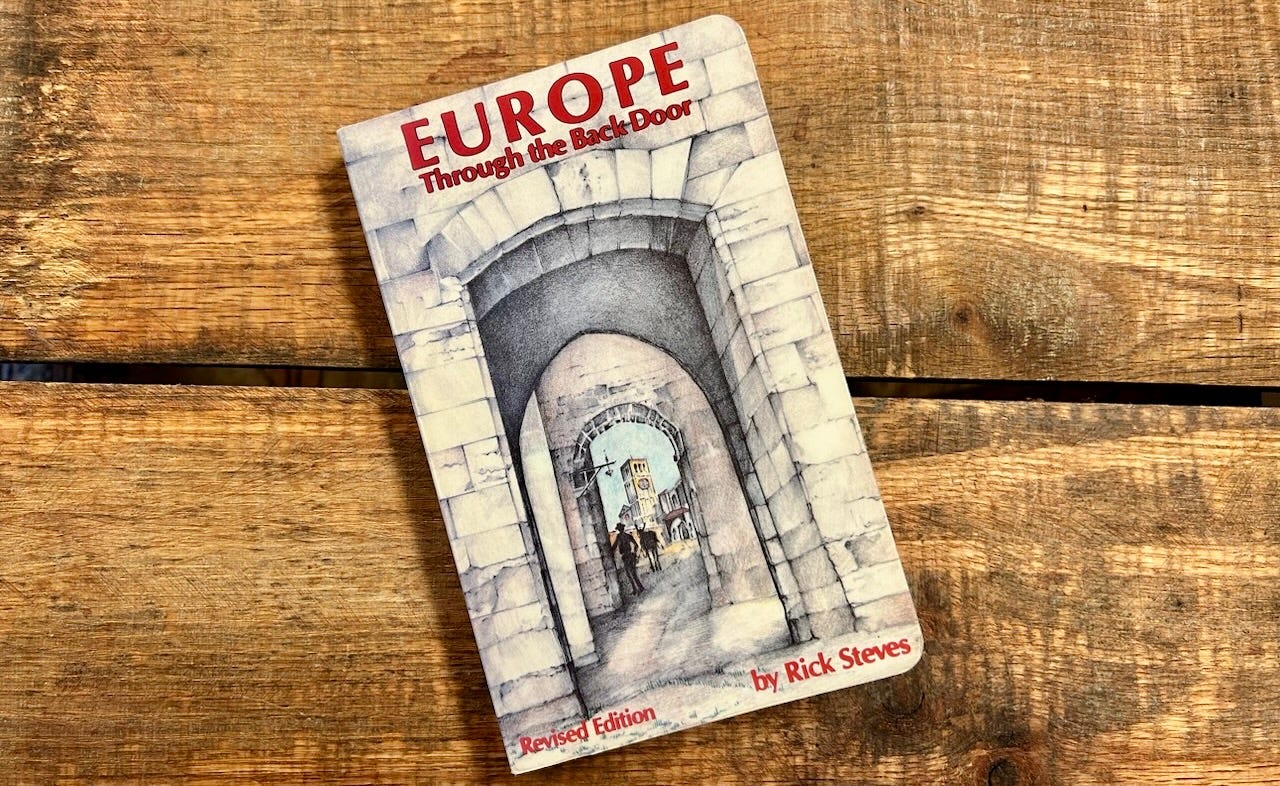

I had wanted to visit these so-called pueblos blancos of Andalusia for a long time—for at least three decades, ever since I read about them in Rick Steves’ classic guidebook, Europe Through the Back Door. As a dumb and impressionable 19-year-old college student, about to head off on a European backpacking tour, Rick Steves as my sherpa. The copy of Europe Through the Back Door that I took with me in 1990 was one of Steves’ early self-published editions that dated to the late 1980s, with hand-drawn maps, grainy black-and-white snapshots, and goofy, hippy-ish illustrations. I still own that dog-eared and marked-up copy. I will always love Steves’ nerdy, idiosyncratic voice and his deeply sincere belief that the world could be a better place if everyone traveled more outside their comfort zone. I revere it as much as any work of travel writing on my bookshelf.

In that early edition, Steves writes breathlessly about the south of Spain. He implores readers to leave the tourist trail, to rent a car and to explore the interior of Andalusia, which he called “wonderfully untouched Spanish culture.” He writes, “All you need is time, a car, and a willingness to follow your nose.”

Steves loved the small towns of southern Spain’s interior, but one stood out above the others. “My most prized discovery in Andalusia is Estepa,” he writes. Estepa is known mostly for its hilltop convent of Santa Clara (“worth five stars in any guidebook, but found in none,” according to Steves). In fact, if the town is known at all in Spain, it’s because the nuns at this convent make a famous cookie that’s eaten at Christmastime. “Enjoy the territorial view from the summit, then step into the quiet, spiritual perfection of this little-known convent. Just sit in the chapel all alone and feel the beauty soak through your body,” Steves writes.

It's surprising how many words Steves commits to Estepa in this old edition of Europe Through the Back Door. He regales readers with anecdotes about “sleeping under the stars” on the convent porch and Estepa’s “evening promenade” where residents “congregate and enjoy each other’s company, old and young.” He loves Estepa so much that he literally transcribes a page from his own youthful travel journal, in italics: “Estepa, spilling over a hill crowned with a castle and convent, is a freshly washed, happy town that fits my dreams of southern Spain.”

My own backpacking trail in those days took me elsewhere—to Italy, Switzerland, France, Germany. I never made it to Andalusia until years later. But because I was such a fan of Rick Steves, I tucked those joyous descriptions of the region’s pueblos blancos away in my memories, vowing someday to visit. Whenever I would see a new edition of Europe Through the Back Door, I would flip to the chapter on southern Spain. Estepa was always there.

More than 30 years after my first backpacking trip to Europe, I realized I would be visiting Andalusia close to the pueblos blancos. Yet when I consulted the most recent editions of Europe Through the Back Door, as well as Steves’ country guide to Spain, I was dismayed to see that all mentions of Estepa had been removed. I looked through several recent editions and found no Estepa. I knew I wasn’t misremembering, that this wasn’t some false Mandela-effect-like memory. After all, as evidence, I had my three-decade-old, dog-eared, hippy edition of Steves’ book.

I needed to know what happened to Estepa. It seemed like precisely the sort of off-the-beaten-path destination that Steves, at least when I was younger, always preached that readers should visit. So, I reached out to Rick Steves, to see what happened to Estepa. Well, not Rick Steves, the man, directly. Rick Steves Europe is now a large travel and media company, and the books they publish are no longer hippy-ish at all. Still, the same day, I got a friendly Facebook message back from one of Steves’ top editors, Cameron Hewitt, with an explanation:

“In about 2015, we overhauled that book and reworked all those old ‘Back Doors’ sections that had been in the book for decades…I imagine Estepa simply didn't make the new editorial cut; we wound up replacing lots of ‘heritage’-type content in that edition with fresher bits of writing from Rick. It was not necessarily because we feel that Estepa is no longer worth visiting; just one of those tough editorial calls you make along the way.”

So Estepa had not been canceled for any noteworthy reason. Rather, Estepa had been a casualty of the same cold, ruthless “tough editorial calls” that many of us in publishing have faced over the past few years—particularly those of us who work the so-called “lifestyle beat,” and particularly those of us who do longform travel writing. The lifestyle beat is a space that’s become increasingly homogenized, full of derivative clickbait tips and listicles driven by social media. Estepa disappeared like so many of the outlets that were once committed to publishing quality travel writing.

In my own life, in one 18-month span, I’d watched two of my anchor publications disappear. In mid 2021, I was told that The Best American Travel Writing, the annual anthology I’d edited for more than 20 years, would be discontinued. The reason given: the publisher was about to be acquired by a larger company, and they were “cleaning up the balance sheet.” Then, in late 2022, I learned that the Washington Post Magazine, the publication where a few times each year I published the best of my travel writing (such as this and this and this) would shut down and cease to exist.

I can’t say either shuttering was a surprise. Travel writing seems clearly to be in decline—both the supply and the demand. For years, during my annual process of reading and selecting for The Best American Travel Writing, I’d noticed a sharp drop in the amount of quality travel writing published in American magazines and newspapers. A decade or two ago, it was no problem to find a hundred notable travel essays and articles. By the late 2010s, I usually struggled to find 50.

More than a genre of writing is being lost by our current era of corporate consolidation. I know in my small corner of the world, I’ve tried my best to amplify voices that were outside of entrenched media structures. But legacy media continues to cut corners as it tries to wring more from underpaid work.

Across publishing, the basic rate for freelance writing has stagnated at around $1 per word for decades (very often less at many outlets). Consider how long this “dollar per word” has been a standard. Ernest Hemingway, filing dispatches for magazines from the Spanish Civil War in 1936, was also paid $1 per word. That 1936 dollar is the equivalent of about $22 in 2023. Even if they’re no Hemingway, today’s writers earn a fraction of the per word rate that writers did almost 90 years ago. What other creators have seen such a precipitous drop for their paid work? Young writers are having to rely more and more on canned press trips, subsidized by brands or regional organizations. It seems that the end result of all this will be that the only people who will have the time and resources to do travel writing will be the same sorts of affluent people that did it in the age of the British gentry on grand tour.

Given all this, is travel writing dead? Dying? When I think about this, I’m reminded that the distinguished UK literary magazine Granta posed this very question to a dozen or so writers in its Winter 2017 issue. Like so many of these faux-provocative questions (“Is the novel dead?” “Is pop music dead?” “Is baseball dying?”) no definitive answer was reached. As Geoff Dyer, who was among the respondents, wrote: “Yes and no. Sort of.”

Much of the discussion dwelled on nomenclature, the idea that the genre’s name —“travel writing”—did not adequately capture what it is to write about place in 2017. “So, what matters to me is not whether a piece of writing is called travel writing,” wrote Mohsin Hamid.

Dyer offers up Miles Davis’ work from the 1970s as a possibility. At that time, Davis no longer referred to his music as “jazz” but rather “Directions in Music.” Said Dyer, “That’s what I’m after: Directions in Writing.”

So yes, this was a pretty weird discussion in the pages of Granta. The simple fact that it was asking the dreaded “Is travel writing dead” question was astonishing enough, but it was especially alarming to those of us who have been ardent readers of both travel writing and Granta since the 1980s. Granta, after all, led a revival of travel writing in the 1980s, advocating for what had become a badly atrophied, nearly moribund genre in the late 20th century. With Bill Buford as its editor, Granta dedicated two special issues to new travel writing, in 1984 and 1989. Legendary travel writers regularly turned up in the magazine’s pages: Bruce Chatwin, Colin Thubron, Martha Gelhorn, Jan Morris, Ryszard Kapuściński.

I can’t overstate how exciting and freeing it was when I first discovered writers like Chatwin or Kapuściński or Gelhorn or Rebecca West or Ted Conover or Pico Iyer. While I was supposed to be focused on fiction in my graduate creative writing program in the 1990s, I found my mind drifting toward travel writing. This was still before the rise of so-called “Creative Nonfiction,” several years before the mainstreaming of the memoir, and a decade before the emergence of personal blogs. Travel writing, in those days, was not a topic of polite discussion in graduate fiction seminars.

In any case, the travel writing published by Granta would inspire me, in the mid-1990s, to create my own journal devoted to travel, Grand Tour, which lurched along for few years, then died and went to small-underfunded-literary-magazine heaven. Out of Grand Tour’s ashes, however, the Best American anthology emerged. In early 2000, I scoured through the travel stories of 1999 along with our first guest editor, Bill Bryson—one of those travel writers who I’d first read in Granta — to gather our first anthology.

I did the same for 22 editions, spanning 9/11, the endless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the lifting of the Cuban travel ban, the Syrian refugee crisis, the presidencies of Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump—chronicling the world as it has been transformed in so many previously unfathomable ways. Travel itself irrevocably changed over that time. I think about what did not exist when I began the Best American Travel Writing anthology: the euro, Brexit, Google Maps, translation apps, Uber, Yelp, so-called “Premium Economy,” boarding passes scanned from iPhones, and TSA Pre-Check.

This evolution is, of course, the sort of thing that’s supposed to happen with travel writing. In my first foreword, to the inaugural edition in 2000, I wrote:

Travel writing is always about a specific moment in time. The writer imbues that moment with everything he or she has read, heard, experienced, and lived, bringing all his or her talent to bear on it. When focused on that moment, great travel writing can teach us something about the world that no other genre can. Perhaps travel writing’s foremost lesson is this: We may never walk this way again, and even if we do, we will never be the same people we are right now. Most important, the world we move through will never be the same place again. This is why travel writing matters.

Maybe the blunt assessment of Granta’s former editor, Ian Jack, during Granta’s 2017 travel writing discussion summed up the way a lot of people think: “Travel writing isn’t dead. It just isn’t what it was.”

Looking backwards at what travel writing “was” has always been fraught. Given the genre’s history of cultural voyeurism, colonialist impulses, and straight-up racism, it’s often not pretty. When literary people ask “Is travel writing dead?” they’re suggesting that the genre is outdated or old-fashioned or in need of an avant-garde “subversion.” I don’t know that this is possible; travel writing is a reflection of its time. Travel writing has existed longer than most other forms of literature, dating at least to Herodotus in ancient Greece. And travel writing has faced criticism for nearly as long. In the first century AD, the Roman essayist Plutarch was already calling bullshit on Herodotus, accusing him of bias and “calumnious fictions.”

Maybe the most subversive, experimental, and most honest “direction in writing” one might pursue is to try one’s hand at classic, traditional first-person travel narrative? That’s what happened during the last real renaissance of travel writing, in the 1980s, the one driven by Granta, and by writers like Paul Theroux, Bruce Chatwin, and Bill Bryson. And don’t forget Rick Steves in that pantheon of travel writers who came on the scene in the 1980s—whose service-minded guidebook writing had always been driven by quirky personal narrative.

When I finally arrived in Estepa, I found exactly what Rick Steves had promised all those years ago. The hilltop convent of Santa Clara is gorgeous, as is the view overlooking the white towns of Andalusia. It was a windy day in February. There were no other tourists at the convent and so I stood and listened to the wind rustle through the tall evergreen trees. Near the convent is a park, where families were having Saturday afternoon picnics. Further down the hill, a cheering crowd watched local kids playing a soccer game.

I wandered down to the town center, through small squares surrounded by orange trees. I passed a group of young people carrying huge ornate decorations into a pretty church. In the town center, I suddenly found myself caught in crowd of children, all dressed in costumes for Carnival (knights, cowboys, superheros, Mario Brothers, anything seemed to go) marching along with a band dressed as jesters and clowns walking on stilts. Afterwards, I followed the parents who crowded into the local bars and I shared a few beers with the good people of Estepa.

Yes, Estepa still seemed to be a lively and just as "freshly washed, happy” as a young Rick Steves found it in the 1980s. It may have been excised from the guidebooks by Rick Steves Europe’s “tough editorial calls,” but the town still exists. Let the TikTokers and Instagrammers—following the posts of other TikTokers and Instagrammers—pour into the bigger, better-known cities. Maybe Estepa is better off now. Maybe it’s been freed from the samsara of tourists who follow Rick Steves?

In telling you the story of my uneventful visit to this Andalusian hill town, I guess I wanted to make the simple point that travel writing is a bit like Estepa. It hasn’t stopped existing simply because of corporate editorial decisions. It’s still there, waiting for someone to enjoy it again.

The impulse to travel and explore—and to write about those experiences—will remain. Pico Iyer (guest editor of The Best American Travel Writing 2004) was one of the writers who took up Granta’s question in 2017. Iyer’s response can stand as mine: “Travel writing isn’t dead; it can no more die than curiosity or humanity or the strangeness of the world can die.”

Thanks for telling me about Estepa. I'll put in on my list. Personal essays like this are what Substack is for. I hope more people come to understand this.

Great essay! I want to get my hands on one of those early Rick Steves guides now.