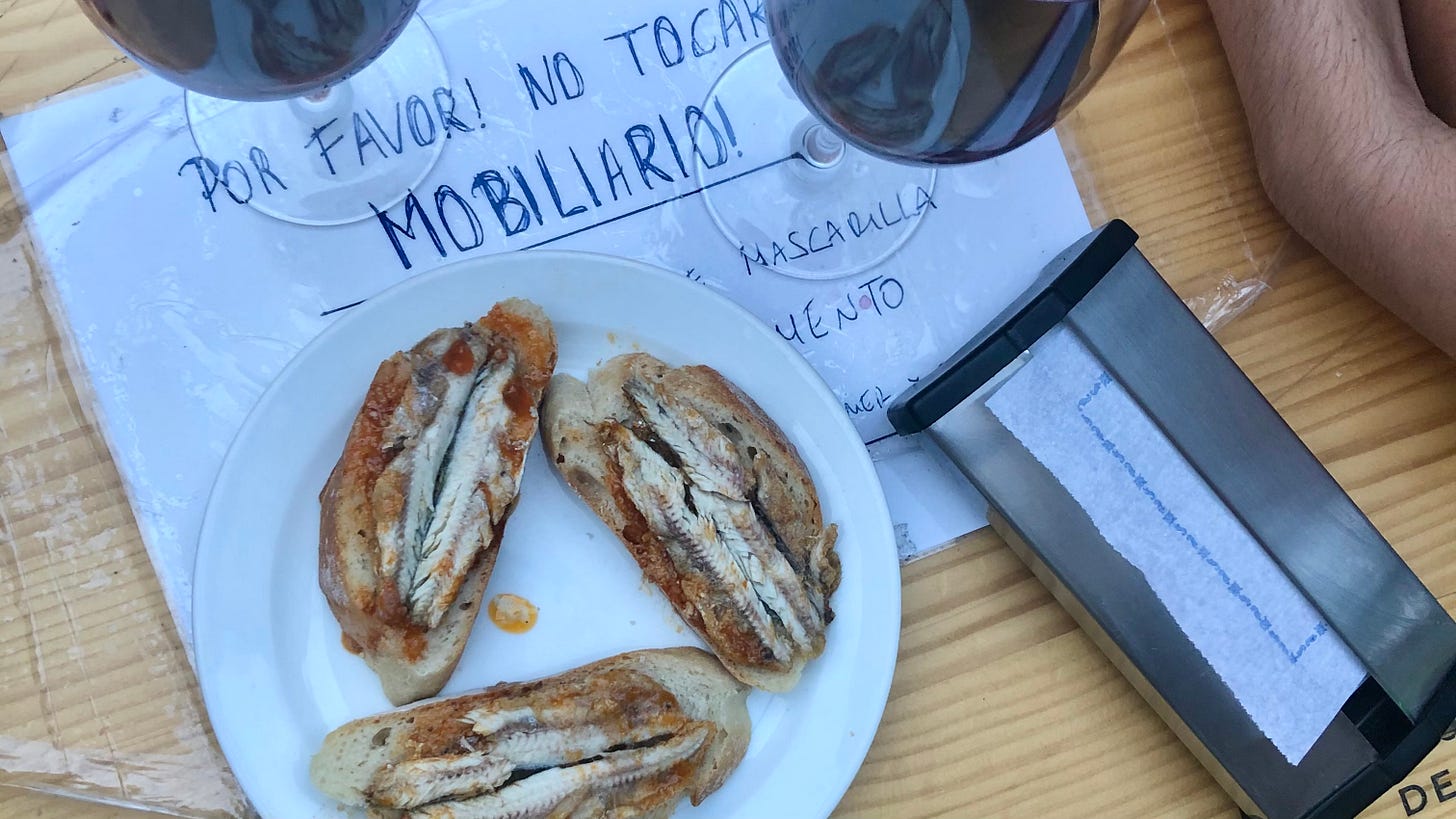

I was happy to see José Andres recently declare “U.S. Tapas Week” in his newsletter. I like thinking about tapas.

Several years ago, Spain’s Royal Academy of Gastronomy announced that the country’s Ministry of Culture would seek protective status for tapas. This protection would come by way of UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage List, which aims to sa…