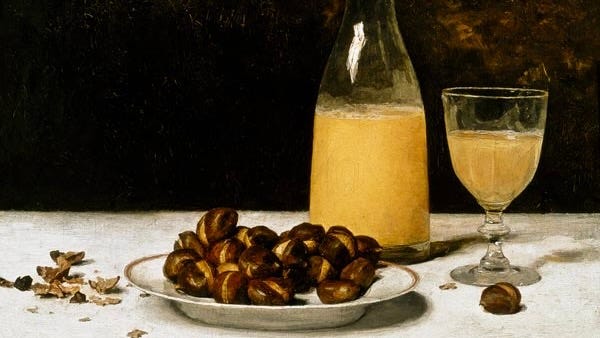

Chestnuts, Winter Whites, and Anemoia

Austria rotgipfler and zierfandler, like roasted chestnuts, evoke nostalgia for a time you've never known. Plus: Make this soup during this holiday cold snap.

Considering the ubiquity of Nate King Cole’s “The Christmas Song” and its opening lyric—Chestnuts roasting on an open fire—I’ve always found it a profound irony that most Americans have never actually eaten a roasted chestnut.

There’s a reason for that, and it’s rather a melancholy one. The America…