Cheese + Grappa, or The End of Pairing

What Spotify Wrapped can and cannot tell us about taste and the ineffable.

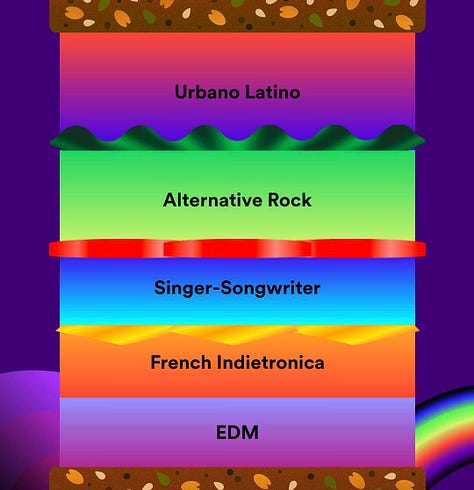

It’s that special time of year, when Spotify Wrapped gets released and the data reveals all of our strange, intimate, embarrassing tastes in music—which we’re then peer-pressured to share publicly. This year, I’m slightly alarmed to see how much reggaeton I’ve consumed in 2023. I am also intrigued that something called “French Indietronica” is among my …