Baby's First Barrel Pick

I finally decided to put my money where my mouth is. The journey toward selecting my very own barrel in the cellars of Armagnac. One you can taste too!

“Taste has no system and no proofs,” cultural critic Susan Sontag once remarked. In his 19th century gourmand treatise, Physiology of Taste, Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin writes, “the space between something called good and something reputed to be excellent is not very great.” Old Nietzsche famously declared: “All of life is a dispute over taste and tasting.”

All of which is my roundabout way of saying something we all know: Tasting, evaluating, and recommending is a dark art. I spent a number of years doing it professionally, as a wine and spirits critic, doing the swirl-sip-swish-spit-scribble with hundreds and hundreds of bottles. The whole enterprise of reviewing and scoring wines and spirits is something I now have fairly mixed feelings about (as I dealt with in an essay for The Drop a few months back). Still, I am grateful to have the experience of tasting in such a focused, professional way, to practice the intense mindfulness and the responsibility of judging someone’s craftsmanship.

Perhaps it goes without saying: Tasting comes with an ego. Yet it comes just as often with the feeling of being an imposter, or at least the feeling that there is still a lot to learn. I am no longer that kind of scoring critic, but the tasting discipline I developed is still relevant.

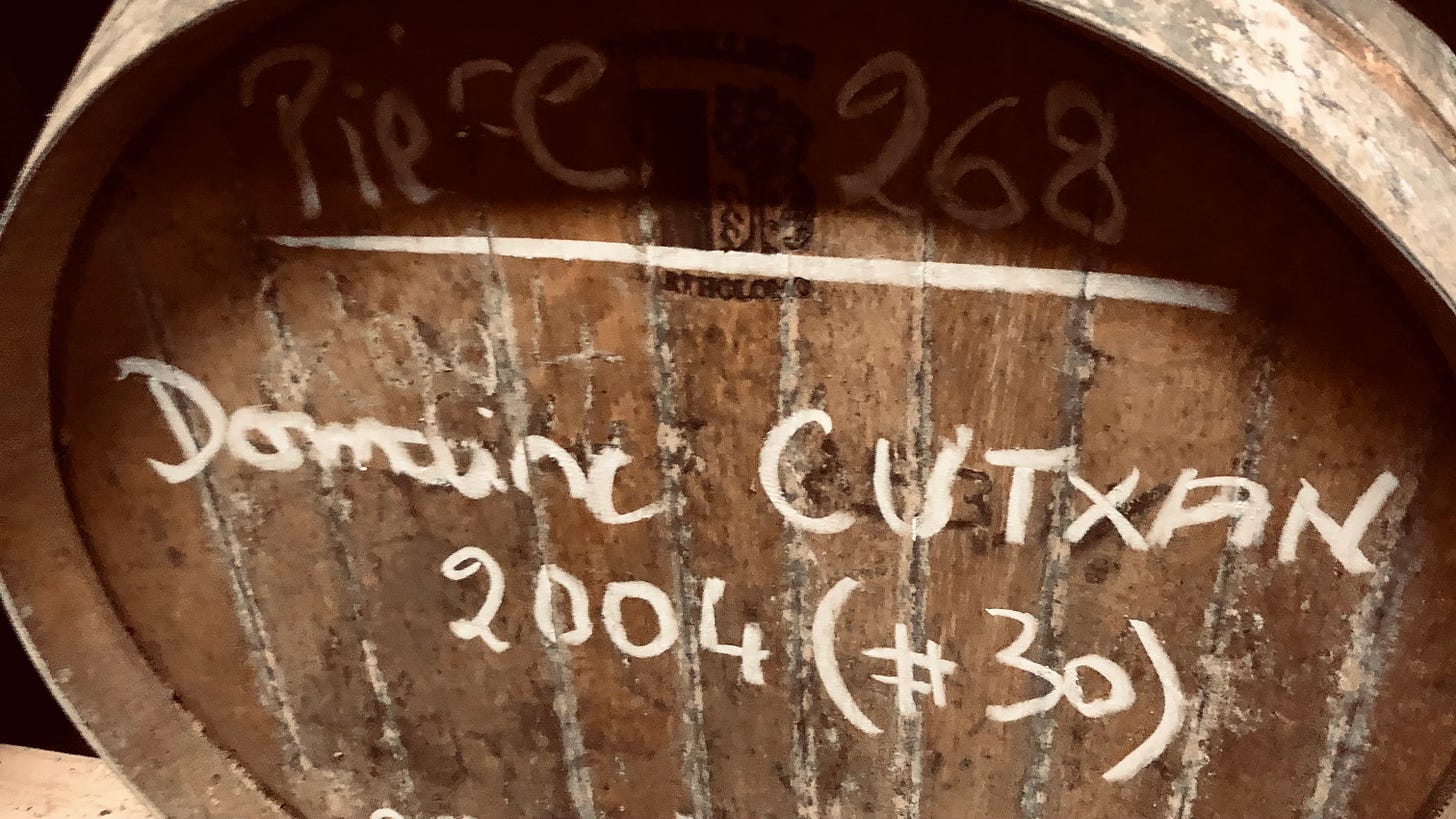

All of which is my roundabout way of saying: For the first time ever, after tasting a lot of Armagnac, I have selected my own barrel, L’Encantada 1997 Domaine Cutxan (Cask #20), a limited-release 23-year-old Armagnac. Now, instead of only being a critic on the sideline, I am putting my own palate out into the world to be evaluated, judged, and — hopefully — enjoyed.

Beyond the obvious reasons for getting into the barrel-pick business, there is also very much a philosophical position I’m staking out with this particular barrel of 1997 Domaine Cutxan. We might go as far as to say this selection is a flaming arrow shot over the ramparts of the current taste trends in Armagnac.

In November, I found myself — along with an amiable group of collectors, fans, importers, distributors, and retailers — at the 10th anniversary celebration of L’Encantada, the Armagnac negociant based in Vic-Fezensac.

Adam Kamin, my retail partner at Off Premise, and I tasted around 50 barrels, most of which were from a new estate, Domaine Cutxan, from which Vincent Cornu, L’Encantada’s unicorn hunter, recently acquired the stocks. Cutxan is a lieu-dit near the town of Cazaubon in the heart of Bas Armagnac. The winemaking family here produced excellent Armagnac for years, but recently made the decision to sell its stocks and focus on their vineyards and wine. Vincent Cornu — in whose palate many collectors have put their trust — thinks these Cutxan stocks rival his very best.

The soaring popularity of L’Encantada releases is undeniable. One could make the case that bottlings of L’Encantada from estates such as Lous Pibous and La Frêche are quickly becoming something like the “Pappy Van Winkles of Armagnac” in the U.S. and elsewhere. They are defining the image of of the spirit, especially to high-end American brandy aficionados.

But as the enthusiasm for expressions like Lous Pibous and La Frêche spreads, and we see more and more barrel picks, a certain flavor profile of Armagnac has emerged as dominant, one that frankly leans too much in the direction of bourbon. I get it: A lot of the eager new converts to brandy are coming from the bourbon world. But I think things have gone too far. I’ve expressed my feelings about this trend before, in a piece for this newsletter titled “Brandy Does Not Want To Be Whiskey,” in which I quote Nicolas Palazzi of importer PM Spirits:

“There’s more Armagnac being sold, but it’s a very specific kind of Armagnac sold to a specific kind of buyer,” says Palazzi. “We’re talking about Armagnac that’s very extracted, heavier on the wood, more powerful, more vanilla. So it’s not very different than the whiskey that people are drinking. We’re selling a lot less classical Armagnac.”

It is no secret that I personally prefer a more classic, old-school style of brandy. I certainly enjoy cask-strength bottlings, many with alcohol by volume pushing up to 47% to 50% or more — and I understand that whiskey-like or rum-like alcohol levels are in vogue. But I believe there’s way too much focus on ABV as a quality indicator. There are many many beautiful Armagnacs with an abv of 41% to 43%, or even lower.

To challenge taste perceptions, our barrel — L’Encantada 1997 Domaine Cutxan (Cask #20) — clocks in at 40.4% abv. Yep, just a .4% above that bogeyman 40% abv level. Yes indeed, that is the cask strength of this barrel, aged on the lower racks of a very humid cellar. When L’Encantada acquired this barrel, Vincent swiftly took it out of barrel, to store in glass demijohn. That natural alcohol evaporation has led to incredible flavor concentration.

Tasting this unique cask immediately blew us away, elegantly unraveling its flavors and aromas: plum, dried flower, dried herb, saffron, turmeric, spice bazaar, antique furniture, old library; classic, textbook rancio; a varnishy, nutty, Szechuan peppercorny finish that goes on for miles. This is a shape-shifter that evolves every time you take a sip. This is a brandy that whispers in a sultry voice instead of shouting. We believe this Armagnac changes the conversation of what “cask strength” means. (Though, yes, of course we would feel that way).

Something that’s not discussed nearly enough among Armagnac fans is the wine, the grapes, the raw ingredient that’s distilled to make the brandy. Around here, we always talk about the grapes. This 1997 Domaine Cutxan cask was distilled from 100% Baco, which is significant.

Baco is a hybrid of Folle Blanche and the North American grape Noah, created in the late 19th century to withstand the phylloxera plague (the technical name is Baco 22A). For most of the 20th century, Baco was the backbone upon which long-aged Armagnac rested. One importer calls Baco “the American muscle car of grapes” that can take decades of oak in a way that’s different than Ugni Blanc or Folle Blanche.

But at the end of the 20th century, there was a problem. As France joined the European Union, hybrid grapes were banned from official appellations. Throughout the 1990s, the French government decreed that Baco should be uprooted by 2010. Throughout the 2000s, there was a lot of heated debate over the fate of Baco. Many smaller producers, trying to gauge the climate, ripped out their Baco vines in favor of Folle Blanche or Ugni Blanc. Ultimately, a group of influential French sommeliers lobbied the EU on behalf of the grape, and the issue was resolved: Baco prevailed and is now the only hybrid grape permitted in a European wine or spirit appellation. Still, during that time of uncertainty in the 2000s, a lot of Baco was uprooted.

It all seems really nerdy—or maybe some real Wes Anderson stuff—but these things matter. If value lies in scarcity or long-aging or traditional-versus-modern styles, then we should be talking more about these complexities.

Of the 50 barrels of Cutxan that we tasted in L’Encantada’s cellars, dating from 1995 to 2006, there was a remarkable, profound difference between the barrels from the late 1990s and the ones from the early 2000s. As always in Armagnac and Cognac, we were given no (read: literally zero) information about the barrels as we tasted. The only thing we could go on was our own palates, and then work backwards toward knowledge.

Only months later (only after we actually bought the fucking barrel) we were told that all 1990s Domaine Cutxan barrels were 100% Baco. Meanwhile, we were told that 2000-2002 Cutxan cask were blends of Baco and Ugni Blanc, and then after 2002 they are mostly Ugni Blanc. (We were not told why. But…like…as I just spelled out…do you need to be Sherlock Holmes?)

For the record, I am huge fan of all the 1990s Domaine Cutxan I tasted. But the dozens of 2000s Cutxan? Eh, they’re a fine beverage. Many of the 2000s Cutxan taste too much like that bourbon-leaning Armagnac of which I’m not a huge fan. Cue Nietzsche.

I realize this may be fundamental critical preference. Looking back at my 2018 report on Armagnac in Vinous, I can see that the L’Encantada bottlings I gave my highest scores to were from 100% old-vine Baco. For instance, the 1982 Del Cassou and 1973 Domaine Sablé, in my mind, were the two greatest L’Encantada expressions at that time. I wish I could now find those two amazing bottles. This is not to say I don’t appreciate, say, 1993 Lous Pibous, made from 100% Folle Blanche and which I then called “a monster of a brandy.” It’s a lovely, lovely spirit, but I rate it slightly below those two other legends.

So I guess I should state what may be an unpopular take: I’m worried that we, as a brandy community, have overvalued Lous Pibous and La Frêche. Why? I haven’t totally unpacked that one yet. But as I follow the discussions on the various brandy forums, I see a defensive pushback against L’Encantada’s new releases of so-called “unknown estates,” such as Domaine Cutxan, at ever-rising prices.

Is Domaine Cutxan an unknown estate? I mean, I guess. But let's remember that L’Encantada, as a company, is only 10 years old — this compared to Armagnac houses that date back hundreds of years. Only five years ago, Lous Pibous and La Frêche were completely unknown. Both are still relatively unknown back home in France.

In the end, I can say that our L’Encantada 1997 Domaine Cutxan (Cask #20) is one of the most unique brandies that L'Encantada will bottle to date. It's like nothing else from them on the US market. It's got an old-school vibe, and doesn't want to be a “French bourbon.” Maybe you will like it, maybe you will hate it. Our hope is that will help spark a further, deeper conversation.