A Question of Taste, A Question of Money

Why does the idea of wine as investment offend so many people?

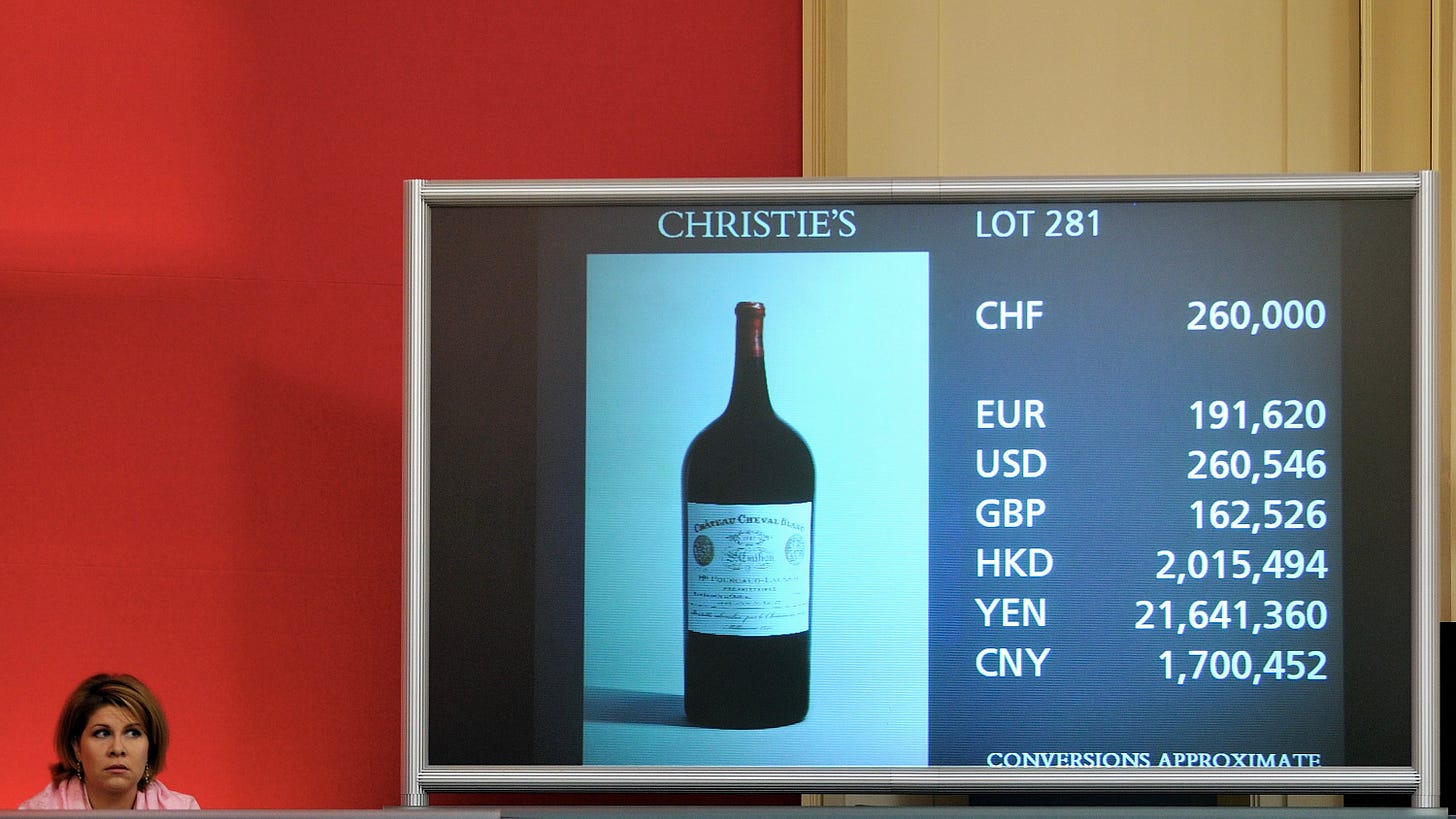

For today’s post, I’m excited to introduce our newest contributor Sara Danese, who writes the excellent In The Mood For Wine, a newsletter focused on investing in wine. In this essay, Sara makes the case for wine as investment. It’s a topic I’ve written about not too long ago (“Why Bother Collecting and Aging Wine?”). What are your thoughts on wine as a…