The Other Vermouth That's Often Overlooked

Call it white, blanc, or bianco. With five recipes (and an ode to Root liqueur, a footnote of cocktail history).

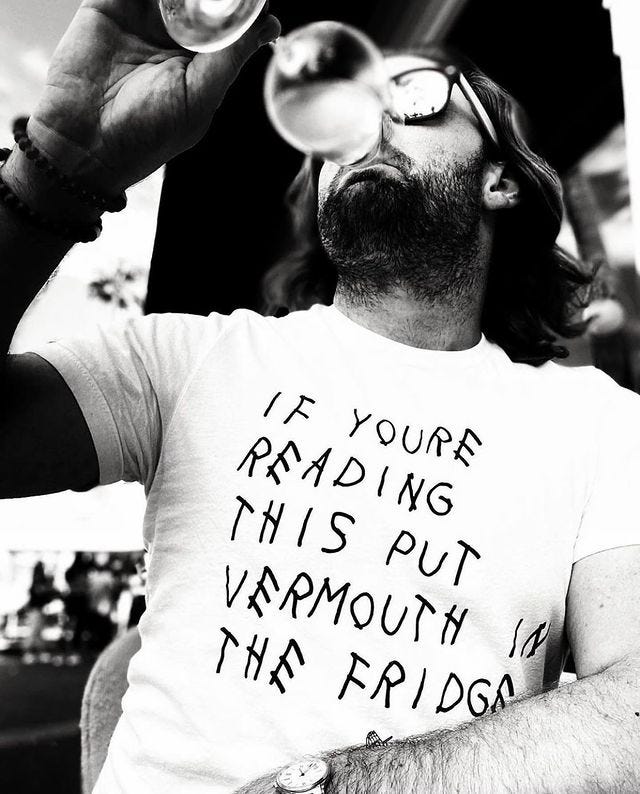

If you’ve read anything about cocktails over the past decade, you’ve probably been warned to store your vermouth in the fridge. By now, this advice is so hackneyed and obvious that (in bartender circles) it’s become ironic, a solid source of memes.

Refrigeration aside, I’m still surprised by what people don’t know about vermouth. Yes, most folks who make cocktails are aware of the distinct differences between sweet and dry vermouth. But I get the feeling that people often forget about the third member of the vermouth family.

In fact, I’d be willing to wager that some of you just stopped for a moment in that last paragraph and said, “Wait. There’s a third vermouth?”

That would be the vermouth known as bianco (if it’s Italian) or blanc (if it’s French)—or just “white” vermouth in the language you are reading. Many people confuse white and dry, though they are two different things. It’s still a bit of a mystery for many.

Not long ago, it was even a bit of a mystery for the pros. No one is more knowledgeable about cocktails than David Wondrich, but even he has written about his early frustrations over trying to recover the correct way to make the classic Cuban cocktail El Presidente. The problem, he reported, was that he kept trying to make the various historic recipes by using dry vermouth and not white. When he finally did use white vermouth: “Eureka! El Presidente, as it was meant to be.”

A decade ago, you saw a lot of white vermouth on drinks menus. It made sense. By around 2012, bartenders had pretty much revived all the classic 19th and early- 20th century cocktails worth reviving, and were scratching their heads about what to do next. Many realized that simply swapping the vermouth was an easy way to do their own riff on a classic recipe. Switch out the dry or sweet for the white, give it a cheeky name, and voila! A new cocktail for the menu.

Lately, I feel like I’m not seeing white vermouth as often. Less and less liquor stores around me, for instance, keep it in stock. Yet when I asked about it on Twitter, I got a lot of passionate responses, and I was happy to see plenty of people still carrying the torch for white vermouth.

Not that white vermouth is anything new. The first white vermouth was made in Chambéry, in the French Alps, by Dolin in 1881. Dolin, in my opinion, is still the best blanc on the market. Another great white option from Chambéry is Comoz.

Still, more bianco vermouth is likely consumed in Italy than France. In fact, more than half of Martini’s sales in Italy are bianco. Go to a bar at happy hour in Milan or Torino, and you’ll see Italians ordering Cinzano or Martini bianco on the rocks, with a twist of lemon.

The difference between dry and white vermouth is significant. White vermouth has distinct aromas—with French blanc it’s floral, citrusy, and piney, with Italian bianco it’s more thyme and oregano with notes of cloves and vanilla. Blanc or bianco, it strikes a unique balance between sweet and savory.

Everyday Drinking’s vermouth expert is François Monti, author of El Gran Libro del Vermut, as well as the new Mueble Bar. About white vermouth, Monti says, “For me, it’s the best option for non-traditional vermouth cocktail spirits—agave spirits, pisco, unaged rums, etc. It’s also fantastic in bitter, amaro-heavy drinks.”

I agree with Monti, and so today I’m including recipes that mix white vermouth with rum, Calvados, Cynar, Old Tom gin, and…Root liqueur. With Root, if you know then you know. And if you don’t, I’ve included a little footnote, an ode to a lost liqueur.

Five White Vermouth Cocktails

Casino Soul

This cocktail used to be on the original menu at The Franklin Mortgage & Investment Company speakeasy in Philadelphia. Casino Soul is a wonderful example of what blanc/bianco vermouth can do to balance a barrel-aged spirit and a bitter. I recommend using an aged rhum agricole from Martinique (such Rhum Clément VSOP)—the grassy, fresh sugarcane notes mingle well with the artichoke-based amaro, Cynar.

2 ounces aged rum

3/4 ounce white vermouth

3/4 ounce Cynar

Orange peel twist

Combine liquid ingredients in a mixing glass. Add ice and stir vigorously, then strain into a cocktail glass. Express orange peel over the top, then add as garnish.

Astoria Vecchio

There are many variations on the early 20th-century Astoria cocktail, itself simply a variation on the martini. My version calls for Old Tom gin and blanc/bianco vermouth. The result here is a rounder, less botanical, take on the martini.

2.5 ounces Old Tom gin

1 ounce white vermouth

2 dashes orange bitters

Orange peel twist

Combine liquid ingredients in a mixing glass. Add ice and stir vigorously, then strain into a cocktail glass. Express orange peel over the top, then add as garnish.

Orchard Keeper

This cocktail pushes the edge of sweetness, but if you use a younger, brasher Calvados, or perhaps a high-proof domestic apple brandy such as Laird’s, you’ll find this to be balanced and bright.

2 ounces Calvados or other apple brandy

3/4 ounce white vermouth

1/4 ounce honey syrup (see below)

Apple slice

Combine Calvados, vermouth, and honey syrup in a mixing glass. Add ice and stir vigorously, then strain into a cocktail glass. Garnish with apple slice.

NOTE: To make honey syrup, combine 1 part honey and 2 parts water in a small saucepan over high heat. Bring to a boil, then reduce the heat to low and cook for 5 minutes. Let cool before using in this recipe.

El Presidente

Perhaps the finest example of a cocktail that demands white vermouth to work correctly. This recipe comes from (who else?) Dave Wondrich.

1 1/2 ounces white rum

3/4 ounce white vermouth

1/2 ounce Dry Curacao, Grand Marnier, or other orange liqueur

1 dash grenadine

1 dash Angostura bitters

Combine liquid ingredients in a mixing glass. Add ice and stir vigorously, then strain into a cocktail glass. Express orange peel over the top, then add as garnish.

Pennsylvania Dutch Manhattan

Named for the unique culture that brought us birch beer, this is a Manhattan variation that uses Root instead of bitters. The trick, as with the other recipes here, is to use the bianco/blanc vermouth. Root is a liqueur based on “root tea,” the original alcoholic precursor to root beer. It’s essentially an American amaro. It ceased production in 2017. But read below for more on its history and where you (might) still find it.

2 ounces rye whiskey

3/4 ounce Root

3/4 ounce white vermouth

Fill a mixing glass with ice. Add the rye whiskey, Root, and vermouth. Stir vigorously, then strain into a chilled cocktail glass. In keeping with the simple way of the Pennsylvania Dutch, this has no garnish.

A Footnote, and an Ode to Root

Root Liqueur was an attempt to replicate early American root tea using ingredients such as birch bark, sassafras, wintergreen, black tea, citrus peels, and baking spices. It was one of those liqueurs that seemed ahead of its time.

Root had a brief moment about a decade ago, and like a lot of new spirits back then, it faded into relative obscurity by the mid-2010s. The producer ceased production in 2017. From what I can see, there is some stock of Root floating around here, here, and here. So if you can find it, grab it, if only because it’s a collector’s item. (Plus, you can make the above Pennsylvania Dutch Manhattan!)

I’m sure that anyone who’s willing to play a little Liquor Store Archaeology in the dusty shelves of local shops could find some bottles of Root. So much of early-aughts cocktail renaissance was based on finding lost ingredients. Why not revive that hunt? If anyone has a bead on where to find Root, let us know in the comments!

I always liked Root. But its Philadelphia-based producer didn’t do a very good job of explaining or promoting it properly. When Root first launched, it was pitched to the spirits market as a “root beer liqueur” and ended up getting shelved with lousy flavored vodkas and other sickly-sweet stuff.

That was unfortunate. Root, although it has the lovely aroma of root beer, was also a bracing 80-proof and had the complex bitterness of an Italian amaro. In fact, you could make the case that Root, especially because of the local herbs used, was an honest-to-goodness American amaro.

What could have been more American than root tea, the precursor to root beer?

Colonial settlers in early America were making alcoholic “root tea” based on Native American recipes—from sassafras, sarsaparilla, birch bark and other roots and herbs—from at least the 18th century. Like the old herbal elixirs in Italy and France, root tea was created as a cure for various ailments. The only real difference between these rustic “teas” and many of the old European liqueurs we know lies in the local plants, herbs, and roots used, and perhaps in the more refined distilling that was done in the old country. Just as herbal concoctions became popular in Europe to drink in non-medicinal settings, root teas soon became a fixture in the taverns of the American northeast well into the 19th century.

However, as root tea grew in popularity, it also became a target for the growing temperance movement by the late-19th century. Root tea was often banned by name as states went dry.

This is where Charles Hires, the pro-temperance pharmacist, comes in. At his Philadelphia drugstore, Hires developed a recipe based on a root tea, but he figured out how to remove the alcohol and then added carbonation. Thus, root beer was born. Root tea, meanwhile, disappeared from American life.

Growing up around Philadelphia, I always understood that we lived in a bountiful land of root beer. Not only did I grow up with root-beer floats, I also was raised on root beer’s red-tinted Pennsylvania Dutch cousin, birch beer (made with birch root instead of sassafras root). If you grew up in the Philadelphia suburbs, there are probably few things that evoke a Jersey Shore summer more vividly than cold birch beer and a slice of thin-crust boardwalk pizza.

Do you remember foraging sassafras in the woods, after finding wild blackberries?