Brandy Does Not Want to Be Whiskey

The bourbon-ification of Armagnac is a terrible trend.

As a long-time lover of Armagnac, as an Armagnac critic, and as someone who was told (by a major importer) that Armagnac sales “went up tenfold” after I published an explainer on Armagnac in the New York Times — I feel I have earned the right to occasionally hold forth on Gascony’s esteemed brandy.

So, I’m just going to put this right out there: I hate the bullshit that’s happening within the Armagnac category right now. For those who don’t already know: There’s a dubious new trend toward what, I guess, we can call the whiskey-fication of the spirit: Armagnac “finished” in whiskey barrels; Armagnac engineered to fit the whims of bourbon drinkers; Armagnac aged in toasty new barrels; Armagnac that’s becoming an anonymous brown spirit with a creme brûlée problem. I HATE it.

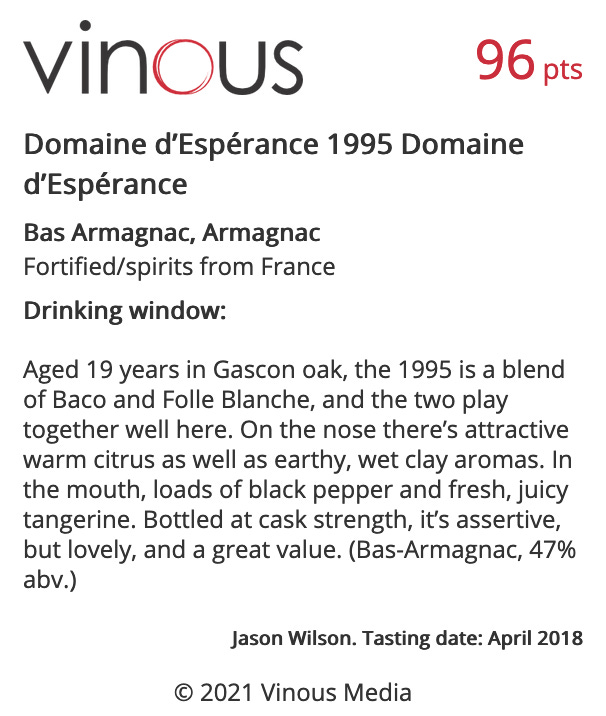

In the past six months, I’ve seen a number of these new whiskey-influenced Armagnacs: from one finished in Islay scotch casks (Bhakta 50 Year, created by a founder of Whistle Pig) to another finished in Bardstown bourbon barrels (Château de Laubade L’Unique) to yet another finished in Weller bourbon barrels (L’Encantada Tattoo). I’ve even tasted a VSOP labeled as “Bourbon Type” released from the legendary Armagnac house Domaine D’Espérance.

“There’s more Armagnac being sold, but it’s a very specific kind of Armagnac sold to a specific kind of buyer,” says Nicolas Palazzi of PM Spirits, who imports both L’Encanata and Domaine D’Espérance — as well as a portfolio full of exceptional (and classic) French brandies. “We’re talking about Armagnac that’s very extracted, heavier on the wood, more powerful, more vanilla. So it’s not very different than the whiskey that people are drinking. We’re selling a lot less classical Armagnac.” Trendy, derivative products are nothing new. It’s when they begin to affect the original that it bothers me.

Believe me, I understand the impulse. Whiskey’s growth is astronomical. Dudes who once spent their coin on Bordeaux and Burgundy now desperately want to become Whiskey Bros. Bourbon prices especially have gone into the stratosphere. So much so that a shadowy secondary market of flippers has emerged, with people selling coveted bottles for thousands. On just a quick search, I found these eye-popping prices: Pappy Van Winkle 23 Year ($5,000); Blanton's Silver Edition Single Barrel ($5,000); William Larue Weller ($1,900); George T. Stagg ($1,500).

If I were an Armagnac producer or importer — peddling a hard-to-understand, hard-to-pronounce product and observing the overheated bourbon market — I can see how I’d be tempted to dump my precious, decades-old eaux de vie into an Islay or Buffalo Trace barrel to capture the attention of Whiskey Bros. I guess I can also see it from the Whiskey Bro POV, as well. I mean, why bother to understand or learn anything about anything, amiright? Money is always the easiest shortcut to connoisseurship anyway.

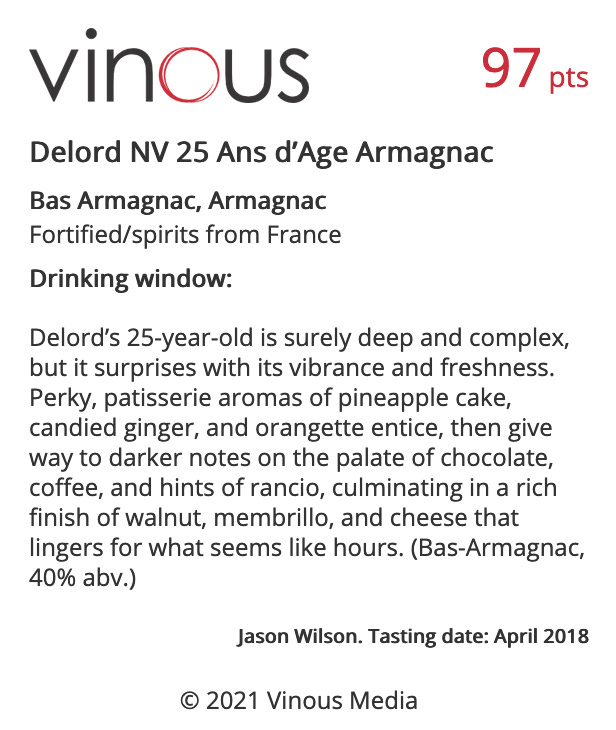

I’m not a fundamentalist or a snob. I’m all for converting whiskey drinkers to the joys of brandy. That’s wonderful. But let’s not lose brandy in the process. Instead, let’s look at how we began sliding down this slippery slope. Then, I will suggest a few bottles of real, classic, great-value Armagnac that you can pick up for a fraction of Pappy.

Stalking the American Whiskey Drinker

Let’s not tiptoe around a basic fact: Ours is not a brandy-drinking culture. When people write about brandy, a famous line from Samuel Johnson is often invoked: “Claret is the liquor for boys; port for men; but he who aspires to be a hero must drink brandy.” By Dr. Johnson’s definition, America is fairly lacking in heroism. Sadly, those who dismiss brandy miss out on an unimaginably delicious nectar full of history and craftsmanship. Armagnac is perhaps the most wine-like of spirits. Factors like terroir and grape variety significantly impact what’s in the bottle. Many American spirits drinkers don’t even realize that brandy is made from distilled wine. (Trust me: I’ve taught enough brandy classes, and I always ask.) That’s also likely why it remains a bit of a mystery in the English-speaking world.

“Brandy as a category is not speaking to a lot of whiskey drinkers because it’s a little more complex, a little more subtle. It’s not in your face,” Palazzi says. “Classic brandy is flowers and fruits. It’s not brash. It’s not slutty.”

Palazzi explained to me how his company’s entire sales model changed during the pandemic. One growth area has been selling single-cask Armagnac to the many whiskey clubs that have popped up all over the U.S. in recent years. “We’re not selling one bottle to a restaurant that sits on the back bar for 18 months,” he says. “We’re selling to a club that drinks an entire cask and then orders another one.”

PM Spirits sends various barrel samples from a chateau to a club, which tastes and chooses its favorite. Then the barrel is bottled in France, shipped, makes its way through the three-tiered system, and is purchased by members at a local retailer. Depending on the age of the barrel, anywhere from around 150 to 300 bottles are produced from each cask, retailing from $100 to $280 — a bespoke craft spirit for a fraction of what a similar, single-cask bourbon selection would be. Palazzi, for instance, recently sold a 41-year-old cask to a club at about $200 a bottle. “If you’re buying bourbon, $200 isn’t going to get you very far,” he says.

Michael Buffa, of the 200-member Orlando Whiskey Society, is one of these converts from whiskey to brandy. Buffa started a side group in Central Florida with about a dozen people, called the Yak Pack, when his taste for Armagnac began to usurp his taste for whiskey. “Armagnac has way more to offer than bourbon, personally,” he says. The Yak Pack has already selected a number of brandy barrels. “The idea is to start creating buying power in brandy,” he says. “In the secondary markets, what bourbon is selling for is absolutely ridiculous. Bourbon drinkers are very susceptible to trends.”

While the Yak Pack quickly gains experience and more exposure to brandy, Buffa notes this knowledge is rare. Whiskey brands have so many more reps out in the field doing so-called education marketing. “Armagnac drinking for Americans is in its infacy,” Buffa says. “There really aren’t a lot of brandy experts.”

That’s where the problem begins. Instead of investing in real brandy education — the relatively organic way that scotch and bourbon and rye got their foothold and became so popular — companies are now trying to shortcut the gap in knowledge by creating dumbed-down Armagnacs that simply taste like whiskey.

The World Does Not Need a “Peaty” Armagnac

There is a spectrum here. On the benign end is something like Domaine D’Espérance’s VSOP “Bourbon Type,” which I recently sampled. This is actual Armagnac that follows the rules of Bureau National Interprofessionel de l’Armagnac (BNIA). They are using newer, toasted French oak barrels that are, let’s say, more “wood forward.” More alarming is something like L’Encantada Tattoo, finished in actual bourbon barrels.

Not everyone shares my sense of alarm. “There is honestly not a ton of difference between classic Armagnac finished in bourbon barrels and Armagnac supercharged in new French oak barrels,” says Palazzi, the importer.

Now, I love Palazzi. He is among the people in the spirits business I respect most, and his brandy portfolio is probably the best in the U.S. But I believe he is splitting a hair here.

Whether the Armagnac is literally aged in American oak that once contained bourbon, or whether the Armagnac producer has felt the market pressure to make their centuries-old product taste more like bourbon to appeal to an American spirits drinker…both feel problematic to me. I’m old enough to remember when people in the wine world lost their minds when French winemakers started making “Parkerized” wines to appeal to the taste profile of powerful critic Robert Parker, and the wine buyers who followed him. Where, as they say, is the outrage?

For now, the BNIA has been quietly navigating the issue. “The finishing question has been a complicated one and there was much debate about it,” says May Matta-Aliah, the organization’s official Armagnac educator. “The BNIA has decided that Armagnac cannot be deemed Armagnac if it has been finished in some other spirit barrel, even if it is French oak. This is why, say, Château de Laubade’s L’Unique with the bourbon-barrel finish is labeled as “Eau de Vie de Vin d’Armagnac.” (Which, by the way, still has the word ARMAGNAC in the name, so…still confusing.)

A step beyond this debate — into the realm of the absurd — is Bhakta 50 Year. Raj Bhakta was one of the founders of Whistle Pig, one of the independent brands beloved by Whiskey Bros. Bhakta bought the entire stock of a traditional Armagnac house, Ryst Dupeyron. He told me that he’d “transferred the majority of it to Vermont,” where it would be finished in Islay whisky barrels. He was releasing his blends a barrel at a time.“Technically it is Armagnac, but I’m not calling it Armagnac,” Bhakta says. Still, all of his promotional material clearly mentions Armagnac as the spirit’s origin.

The Bhakta 50 that I tasted, “Barrel 4,” is made up brandies dating from 1868 through 1970. That means that these spirits had spent decades (a century!) aging quietly in the cellars of Gascony — only to be now blended and put into a barrel that had been used to make Scotch. They had only spent a few weeks in the Scotch barrel, but the effect was dramatic: Peaty, smokey, salty. I have tasted literally hundreds of Armagnacs, and if you hadn’t told me this was Armagnac, it would have been nearly impossible to tell you what the spirit lying beneath the wood was. This was simply a smokey brown spirit that one could bottle with an eye-catching age statement — 50 years old! — and sell to a spirits drinker who could afford the $375 price tag.

When I spoke with Bhakta, I wanted to know why he couldn’t have just blended and bottled Armagnac with the priceless stocks of Armagnac he had acquired?

“Why build up a category that I can’t use long term?” he said.

“Well,” I said, “There are people who actually love Armagnac.”

“Yeah, like four people,” he replied, with a laugh. Then he said, “I’m torn. I love Armagnac. But the rules are confusing.”

What would he call this new not-Armagnac category, I wanted to know.

“It’s Bhakta. Bhakta is for the American whiskey drinker. The American whiskey drinking is dying for something new. He just doesn’t know it yet,” he said. “Armagnac just doesn’t have much brand value.”

And there you have it, folks. I actually appreciate his sheer hubris and candor in a perverse way. But to be clear, it’s an annihilation of the category. Where does that leave those of us who do love Armagnac (all four of us apparently)?

I am no stranger to tilting at windmills (see also: anti-influencer). Brandy lovers like me have been waiting patiently for brandy’s moment (just like tequila, gin, rum, and whiskey before it). Still, I can’t help but feel we’re at a precarious place. If brandy’s “moment” means that we’re going to basically get bourbon with a French name…will it be worth it? I don’t have any answers to this, and so I guess I’m raising the issue now so we can discuss it.

I just saw this article for the first time. I’ve been railing against Bhakta and similar destruction of Armagnac since I first heard of it. Traditional Armagnac is a true treasure that we can’t allow to be lost!

The sad deracination of Armagnac.